Photography provided a guaranteed witness to the burgeoning genre of performance art in the 1960s, when restrictions in Socialist societies sometimes created a far different relationship between performance and documentation than in the West. Art historian Amy Bryzgel highlights several key works of Central and Eastern European performance art from the MoMA Collection.

by

Artists have been reliant on photography and video cameras to document live works of art, or performance art, most consistently since its emergence in the 1960s as a fully fledged genre. There are numerous debates regarding the essence of performance art. For Peggy Phelan, the live event takes primacy. As she states, “Performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.” For Philip Auslander, however, a work of art becomes a performance the moment is it performed for the camera. For him, “The act of documenting an event as a performance is what constitutes it as such.”

Auslander and Phelan were writing primarily about Western artists—such as Cindy Sherman, Hannah Wilke, and Yves Klein—within whose work are numerous examples of performances that were staged in front of a camera as opposed to a live audience. In the former Communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, however, in many cases, artists performed for the camera out of necessity, as the restrictions of various political regimes prohibited any kind of public display or performance on the streets.

The 1970s were a challenging time for artists in Czechoslovakia. Following the liberalization of the 1960s, and the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops in 1968, which brought the Prague Spring to an end, the government sought to bring Czechoslovakia back in accord with the Soviet party line; what followed was a period referred to as “Normalization.” There were consequences for artistic transgressions, including expulsion from the state artist’s union, and so artists contained their experimental activity by sharing it only with close and trusted friends, in private spaces—for example, in the basement of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, where one artist (Petr Štembera [b. 1945]) worked as a night watchman, or the countryside, which was less subject to surveillance than the city.

- Jiri Kovanda: Contact, September 3, 1979. Gelatin silver print. The Museum of Modern Art New York. Committe on Photography Fund and Committe on Media and Performance Art Funds © 2016 Jiri Kovanda

Czech artist Jiří Kovanda (b. 1953) found another solution, however, producing Minimalist actions on the streets of Prague, which were either captured by the camera, or simply recorded in a note written by the artist. He managed to execute these actions in public because they were barely perceptible as works of art; in most cases, only he and his photographer were aware of the artistic work taking place. And it was only the artist’s photographic documentation that framed the actions, demarcating them as art.

For example, in one of Kovanda’s first public actions, xxx 19 November 1976. Prague, Václavské náměstí, which has become iconic in reproductions, the artist stood immobile on the sidewalk, facing the oncoming pedestrians with his arms outstretched as if being crucified. When asked how he managed to complete such an action, he commented that it lasted only for a few brief seconds, long enough for his photographer Pavel Tuc to snap the picture.

Kovanda quite rigorously and consistently documented his actions by dedicating a sheet of paper to each one, titling and dating it, and sometimes including a short description, photograph, or series of photographs. Nowadays, these documents have acquired monetary value, however in the Communist period, they simply served practical purposes: they functioned as evidence that the performances had taken place, and were used to show others the performance, after the fact.

In Contact (September 3, 1977), Kovanda walked down Spálená and Vodičkova streets in the center of Prague, casually bumping into other pedestrians as he went; his photographer was positioned strategically across the street to capture the physical exchange between artist and passersby. Of course, to the unaware bystander, this action appeared to be nothing more than the everyday occurrence of a clumsy individual’s stumbling into those passing him on the street, an event not warranting anything other than a discrete apology. Kovanda’s gestures, however, echo those of the secret police—which were already taking place on the streets—the photographing of everyday life through surveillance. In Contact, he placed himself in the position of the surveilled, by co-opting a friend to play the role of the secret police and to document those with whom Kovanda interacted.

Though it is possible to read these performances through a political lens, the artist explains that his personal motivation for carrying out many of these performances was to overcome his own personal shyness. In his performances, he does so through interactions, attempted meetings, and eye contact with innocent bystanders on the street.

The artistic atmosphere in Bucharest under Nicolai Ceauşescu was not dissimilar to that in Prague in the 1970s. Artists such as Ion Grigorescu (b. 1945) and Geta Brătescu (b. 1926) took refuge in their studios, creating performances that were usually only witnessed by a photographic lens.

Art critic Ileana Pintilie has described Grigorescu as using the camera as an audience, or witness to his actions, which are performed in his studio or the countryside. Writing about his film Male and Female (1976), she states, “If this film was not necessarily conceived for public presentation—which seems obvious—then the artist must have ascribed such a role to the video camera, to the lens which should record the image and which becomes a ‘partner’ of his explorations, a sort of ‘accomplice’ of his most intimate thoughts and states of excitement, mental and physical.” Because his performances took place in the privacy of his studio in Communist Romania, they were largely unknown in the wider Romanian context, or even artistic context, and have only recently begun to gain recognition and visibility. Consequently, the photographic and filmic documentation of these works has been crucial in preserving this unique piece of art history.

- Ion Grigorescu. Boxing, 1977. 8mm film transferred to 16mm film (black and white, silent), 2:27 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2016 Ion Grigorescu

But the artist had other reasons for co-opting the camera in his performances, for using it mainly as a tool of experiment, such as in manufacturing impossible scenes. One can witness this in Boxing (1977), in which the artist created a double-exposed filmic image of himself boxing with himself. And in Dialogue with President Ceauşescu (1978), he uses the camera and the double-exposed image to create something even more impossible—a conversation or interview in which the artist, as himself, questions the leader of his country, whom he also plays, but wearing a Ceauşescu mask. Although confined to his studio, in these instances, the performance for the camera was not only the result of necessity, owing to the sociopolitical situation, but also a vehicle that enabled him to create fictitious scenes and dialogues.

- Geta Brătescu. Towards White (Self-Portrait in Seven Sequences), 1975. Gelatin silver print, 2 3/4 x 15 15/16″ (7 x 40.5 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Modern Women’s Fund. © 2016 Geta Brătescu, courtesy Ivan Gallery Bucharest, and Galerie Barbara Weiss

For Grigorescu’s colleague Geta Brătescu, the studio was a sanctuary, and it was through this space that the artist defined herself. The studio even features as a character in some of her performances. The photographic performance Towards White (Self-Portrait in Seven Sequences) (1975) consists of seven closeup photographs of the artist’s face. The artist gradually covered her face with cellophane, so that by the final image, the viewer sees only a white square, a blank canvas—resulting in the artist’s literally disappearing into, or merging with, her work. A subsequent and similar piece, Toward White (1975), comprises nine photographs, each documenting the gradual papering over of her studio which, by the end of the series, is entirely white, with the artist covered in a costume of white paper, with white paint on her hands and face. In the final frame of this performance, the artist has become one with her studio, the space of her creation. About this precious space, she said: “Whenever I try to make philosophical speculations I experience embarrassment, the wince of the amateur. I save myself by repeating to myself that everything I say originates in my studio, the artist’s studio.” Just as with Grigorescu, her studio is not a space of confinement, but rather a place of freedom, and the lack of ability to perform publicly does not limit the artist. Instead, the photographic lens enables artistic experiment to take place.

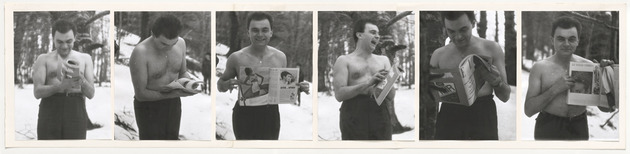

- Tomislav Gotovac. Showing Elle. 1962. Six gelatin silver prints. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Photography Fund. © 2015 Tomislav Gotovac

Croatian artist Tomislav Gotovac (1937–2010) created his first semi-public happening, Showing Elle, in 1962. This was a photographic performance on the Slemje mountain outside of Zagreb. On the snow-covered mountain, he removed his shirt and thumbed through a copy of Elle magazine, showing some of the layouts to the camera. In one image from the performance, the artist shows an underwear advertisement, the female model as semi-nude as the artist. Gotovac created a doubling of objectification, as he makes himself the object of the photograph in the same manner that the woman in the advertisement has been reified. Two years earlier, however, in 1960, the artist created a series of five photographic performances reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills series, in which he dressed up and pretended to be an actor in a French film. Although not categorized as a performance, the piece, entitled Heads (1981), functions as an early instantiation of performativity, not to mention a surprising precursor to Sherman’s work of nearly twenty years later.

Gotovac, who was first and foremost a filmmaker, is known to have said that when he opened his eyes in the morning, he saw a film. Rather than seeing the images that document his performances as photographs, one could think of them as film stills, or of the performance that is life. Unlike in Romania or Czechoslovakia, public street performance was common in Yugoslavia, and Gotovac himself enacted many performances in which he walked naked through the streets of Zagreb. His performances for the camera, however, are just that—performances that could only be conveyed by being captured through the lens. For artists across Central and Eastern Europe, where the possibility to perform in public spaces varied from country to country, the camera offered a guaranteed witness to performative activity, not only enabling and facilitating artistic experiment, but also preserving it for posterity. It also opened up new venues for creativity, regardless of the limitations placed on artists and the public space.

via Post notes on modern and contemporary art around the globe