Artists: Marko Mäetamm, Flo Kasearu, Alexei Gordin, Madlen Hirtentreu, Sandra Kosorotova, Tanja Muravskaja, Evi Pärn, Tanel Rander

Title: east end(s)?

Venue: Põhjala Factory, Tallinn

Curator: Maria Helen Känd

Project manager: Minna Triin Kohv

Visual identity: Henri Kutsar

Photo: Felix Laasmäe

The group exhibition ida ots(as)? / east end(s)? / край Восток(у)? examines and reflects

upon the socio-psychological experiences and status of a society located in North-East

Europe. Eight Estonian artists present their approaches to the topic in diverse mediums, and

thereby create a complex offering for an open dialogue.

Historically, Estonia was ruled by different foreign powers, including Sweden, Germany,

Denmark and the Russian Empire, until 1918 when the Republic of Estonia was established.

Following a few decades of independence, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union,

regaining independence in 1991. Back then, the yearning for freedom was so strong, that

this shared feeling of endurance conceived a common saying: “to be willing to eat potato

peels” – that Estonian people would endure absolute poverty to attain freedom. Thus, the

potato is symbolic of this spirit of searching for belonging to Western society, and the

multiplicity of the layers of this daily vegetable serve as great inspiration. The potato is

ironical, while it is connected to poorness and a certain simplicity, it never loses that earnest,

emblematic characteristic of austerity and strength. That is why the potato is a central motif

of the exhibition.

After securing statehood, the government strove to become a member of the EU, which was

achieved in 2004. Since then, the public agenda has been to include Estonia in the already

existing image of Northern European countries and promote Estonia as a digital success

story and a tech-savvy nation. Alongside rapid development, Estonia has been grappling

with severe socio-economic problems, such as the biggest gender pay gap in the EU, the

relative poverty of a quarter of Estonia’s population, and issues related to the integration of

non-Estonian speaking communities.

Estonia is in the process of finding its identity as an open-minded progressive nation with

roots in folklore, whilst having to accept the disruption of the time under Soviet occupation.

Estonian society now consists of diverse nationalities, mainly Estonians and Estonian-

Russians, rediscovering their traditions. This can be healing, but there is a danger of being

stuck in the past and using this heritage as dividing nationalism. Additionally, economic

inequality and historical traumas prevent societal unanimity. In order to be overcome, these

traumas need a collective sense of strong social structure, which is formed by the state and

its citizens finding common ground in a dialogue. This exact moment in time feels like a

sensitive turning point: we are searching for healing and restorement, but at the same time

we must open up to the world, which touches upon old wounds, to ensure the sustainable

perspective needed to build identity from roots to the future. This topic was selected,

because I believe that we need more time, conversations, and opportunities to share our

positions and opinions about this highly complex occurrence.

The current tensions that exist generate inner conflicts, thought processes, and emotional

expressions, which result in a powerful creative impulse. The works selected present

different positions to address the issues and possibilities around one’s identity, our identity,

which is the key focus of this exhibition. The exhibition entails socio-geographic, temporal,

and psychological aspects of borders and asks: How is our identity shaped by inner and

outer expectations? Is there a chance that we can preserve and resolve ourselves to

develop our identity, even though we are part of the EU and, due to this, constantly

confronted with the image and the standards of the Western world?

In the following sections, I share some information on the exhibited artworks in order to

support a potential dialogue. Also included are my own personal interpretations in

connection to my curatorial approach, sometimes using the artist’s sentiments. However, be

sure not to take my words as the only, or singularly complete, understanding of the works

and the multilayered questions raised about the history and status of identity in Estonia.

Marko Mäetamm‘s work, entitled “Estonia”, was chosen for the Permanent Representation

of Estonia to the European Union in Brussels. It beautifully displays the irony and ignorance

our nation is often confronted with. The stylistic focus on the written word offers a low-

threshold approach and, with this, immediate engagement with the content. Very much on

point Mäetamm characterises the standard small talk situation, the urge to be polite and

keep the dialogue alive, the slightly too long pause between questions and answers, and the

inappropriate comparisons, which are tolerated because of the speaker’s lack of knowledge.

It is an honest and transparent work, as black and white as some of the minds we are

surrounded by.

The soliloquies of the man walking through the rain, disconcertingly bouncing thoughts back

and forth. In Mäetamm’s words: This work is my attempt to describe how complicated it is to

explain why we feel the way we feel and behave the way we behave. We, as people, often

carry the patterns of our culture and history, we are connected to the collective memory of

our country and the people who lived before us. We are made of a certain material and this

material has a very strong influence on us.

Already being iconic in itself – the four nude photographs of Tanja Muravskaja that are part

of the seven-photo series “Positions” display young Estonian artists posing with the nation’s

flag. The confident and strong self-presentation overtakes the generalising character of the

flag by individualising its display. The shape and structure of the flag is defined by the

decisions of the individual and not the other way around. Bare skin usually reflects a certain

vulnerability, but here it stands out as unveiled strength, the new generation freely

expressing their position towards questions of nationalism and identity.

In her second work “From a clean slate” Muravskaja amazes with a similar simplicity in her

aesthetics. The installation consists of two mannequins in a walking posture, wearing white

clothes with a red sculptural structure on their backs. The anonymity of the figures, the

cleanliness of the wardrobe in relation to the abstract and high-contrast structure merge into

a futuristic impression. Is this a scenario of future humans? What does the red framework

symbolise? Is it “Our Past” from which we can’t liberate ourselves? Or Is it a burden or an

opportunity for our identity to keep the balance between the past and the future?

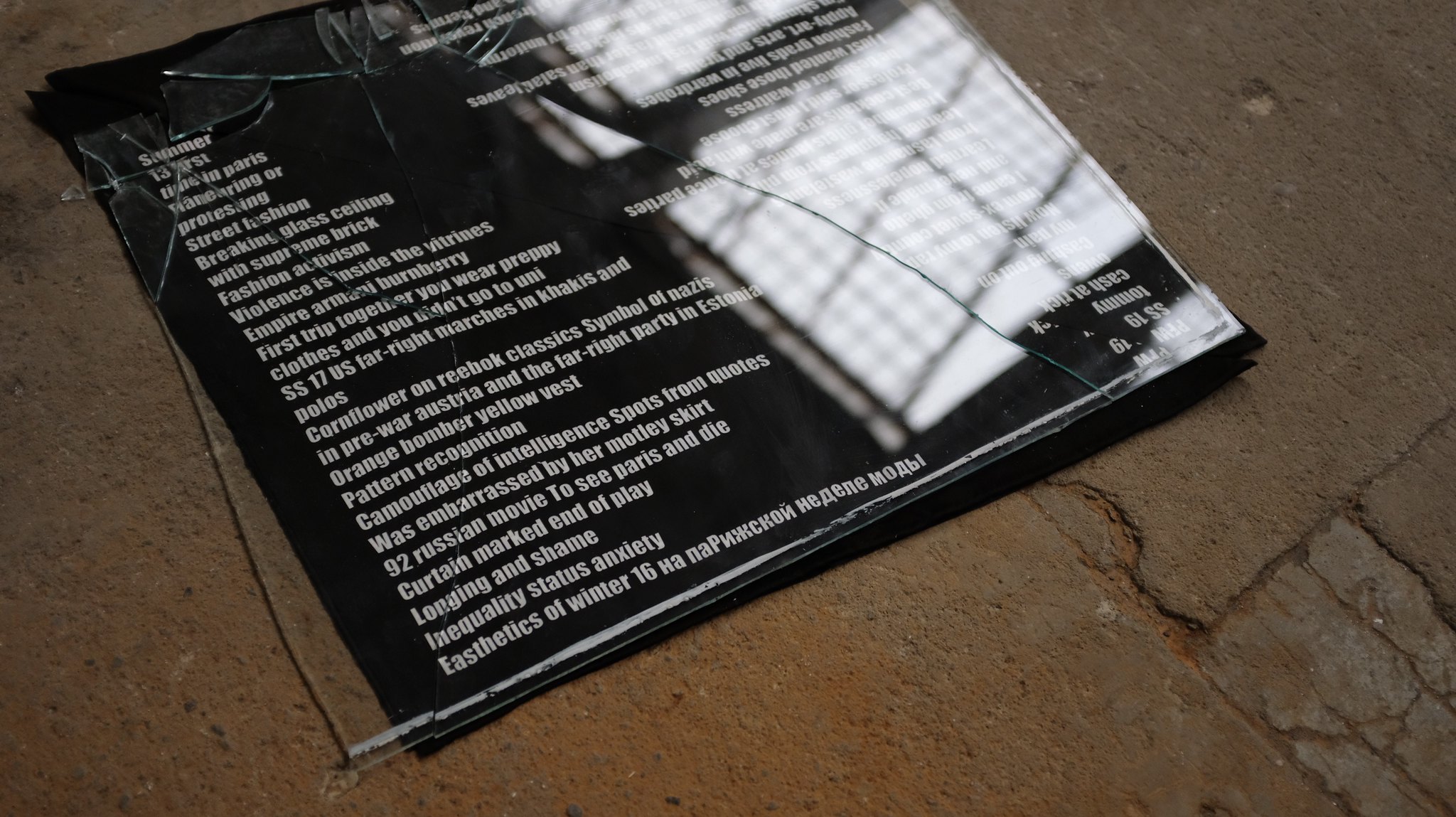

Sandra Kosorotova‘s work “Slavinavia” presents a synthesis of the Scandinavian with the

Estonian flag and reflects the multilayered process of expressing identity through staged

images. At the time of its making, there was a controversial discussion about the expression

of Estonia’s identity through newly defined imagery, which set the context of the work.

Scandinavia hereby represents the longing for affiliation with the group of so-called West- and North European states. The danger in focussing on ideals and imaginations lies in the

disregard towards the acknowledgement of Estonia’s past and its own process of finding its

identity. To adapt because of a wish to belong leads to overlooking and results in a distant

and strange image with some familiar aspects as on Kosorotova’s flag. However, this is far

from an organic development of identity and appears like a shortcut in this long and intense

process.

The work “Bananas” reflects on the usage of Eastern European clichés in brand imagery.

Kosorotova criticises stereotypes that intentionally utilise these defined images to achieve

recognition in an international context. A rap song is printed on a square shaped silk fabric

and addresses the interplay between fashion, Western capitalism, populism, and self-

presentation. To be a part of the group you need to look and be like the desired Western

European ideal, even though it means sticking to general profiles instead of individualism.

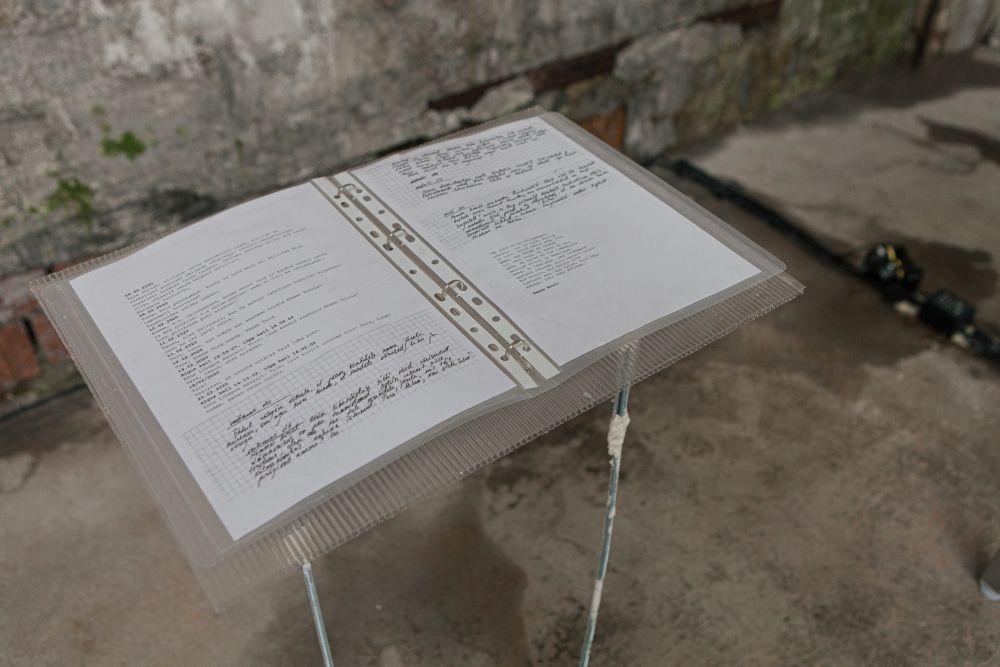

The central topic of the work “A trembling piece of lard” by Madlen Hirtentreu is the

territorial constraint of both mental and physical space, from which she constantly invents

new ways and means of manipulation. Her kinetic sculptures, installations, and

performances are often characterised by Frankensteinian techniques, absurdity, and an

eclectic choice of materials. Materials often serve as the role of a recorder. In this multimedia

work, she stages bones and flesh on a table. By pushing a button, the viewer interacts with

the work and starts the kinetical installation. A transcribed conversation with the seller of the

installation’s bones is in dialogue with a poem by Hasso Krull. This connection creates an

ironic and humorous moment that results in a sensitive absurdity. Memory, historical

traumas and grief are brought together and benefit in the complex combination of materials

and content that layer a certain ironic lightness.

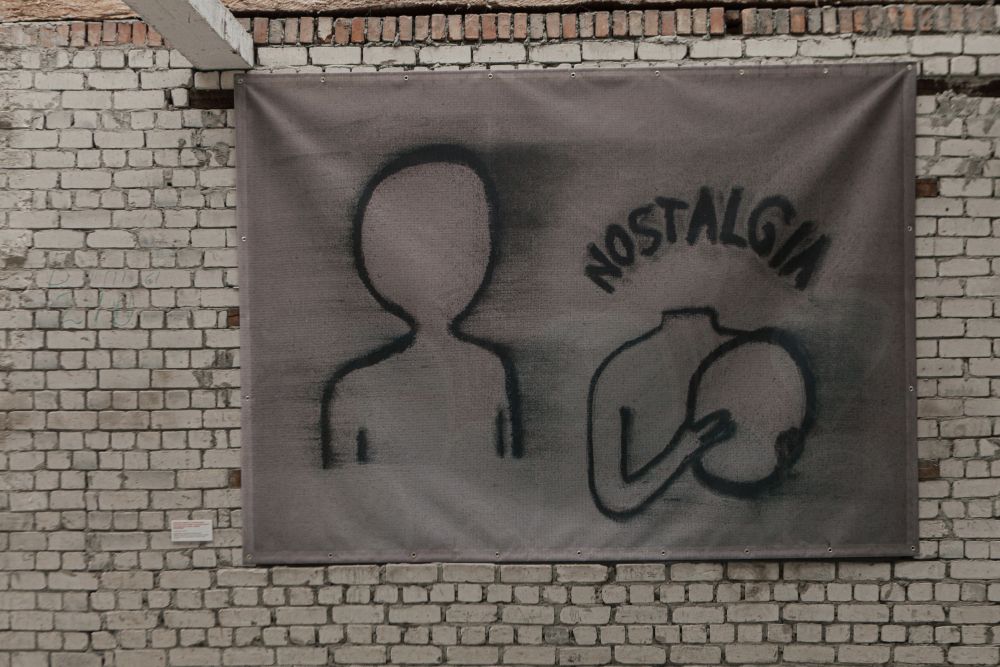

“Nostalgia” is a part of Tanel Rander’s conceptual work the “Guillotine Effect”, which

observes the transformation of East European in the late 80s and early 90s. The Guillotine

was the foundational instrument of democracy. As Western democratic powers reached the

ruins of socialism, guillotines were brought to the streets. No human heads were falling

there, but the heads made out of bronze – the symbols of totalitarian regimes, while the

actual elite of this regime only slightly transformed into the elite of capitalist society. Starting

from this analogy the work observes the Eastern European transformation and detects a split

subjectivity – with the head located in the West and the body located in the East, inner

harmony and balance is impossible. This division can lead to nostalgia, which acts like filler

and a reminder of better times for stability, but shifts focus from the current situation to a

dreamy version of the past.

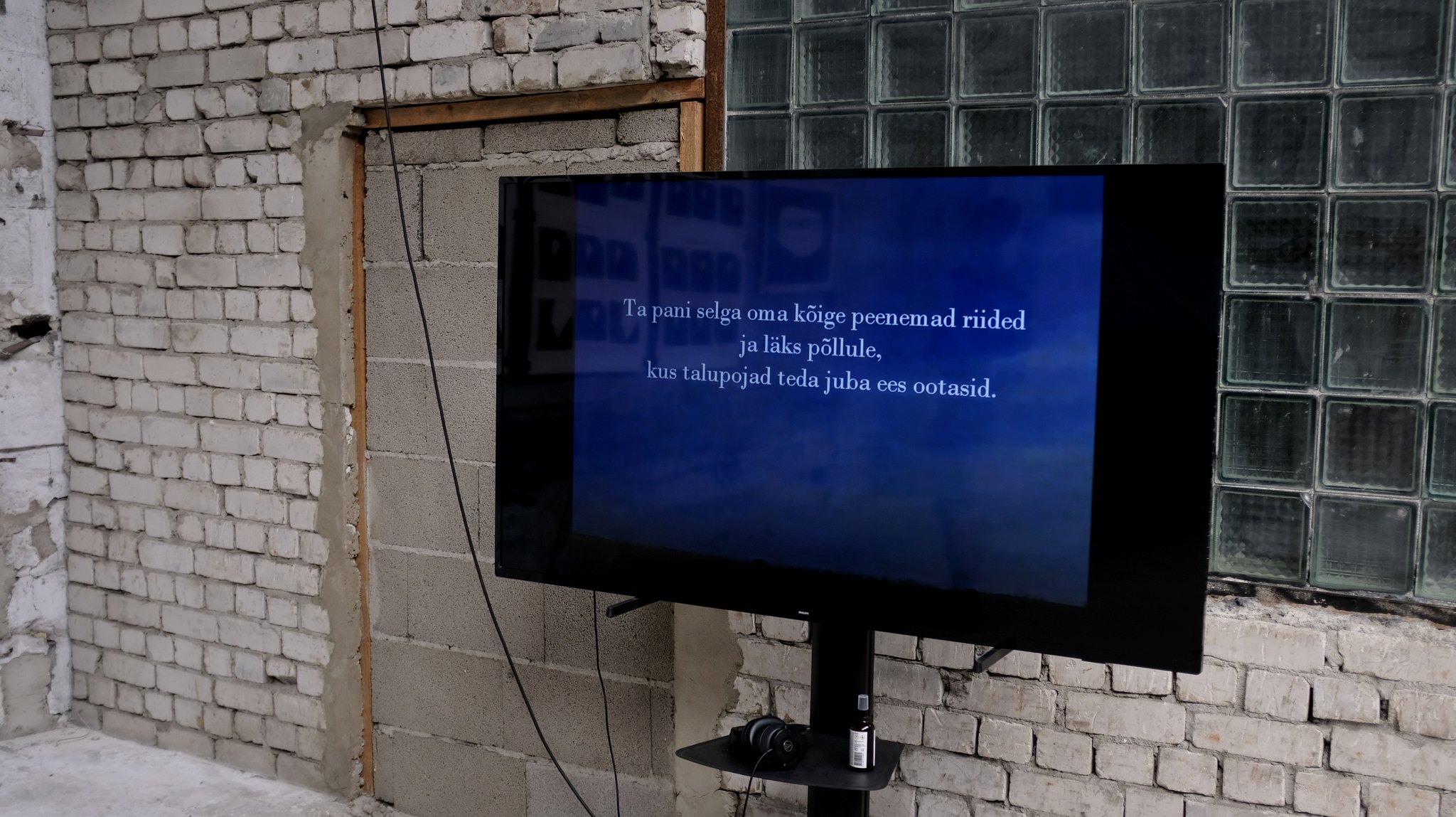

In the video works “The Strategical Planning of Transformation” and “Potato in the pocket”

Rander uses the potato as a symbol to critically approach historical phenomena, such as the

introduction of Western cultural values to Estonian peasantry by noblemen. The second

video explores his childhood misconceptions about Estonian political status and its

relationship to the West. Both of the videos make an impact in their simplicity and strong

metaphors.

Flo Kasearu’s floor installation “International Fun” recreates the flag of the European Union.

On the familiar royal blue, the stars have been replaced by banana peels introducing an ironic tone to the intended greatness of the flag as a unifying symbol. Reality, however, is

different, as this union is fragile in its structure, and the members often slip slapstick-like

through the ideal of togetherness, while a single misstep could lead to drastic

consequences.

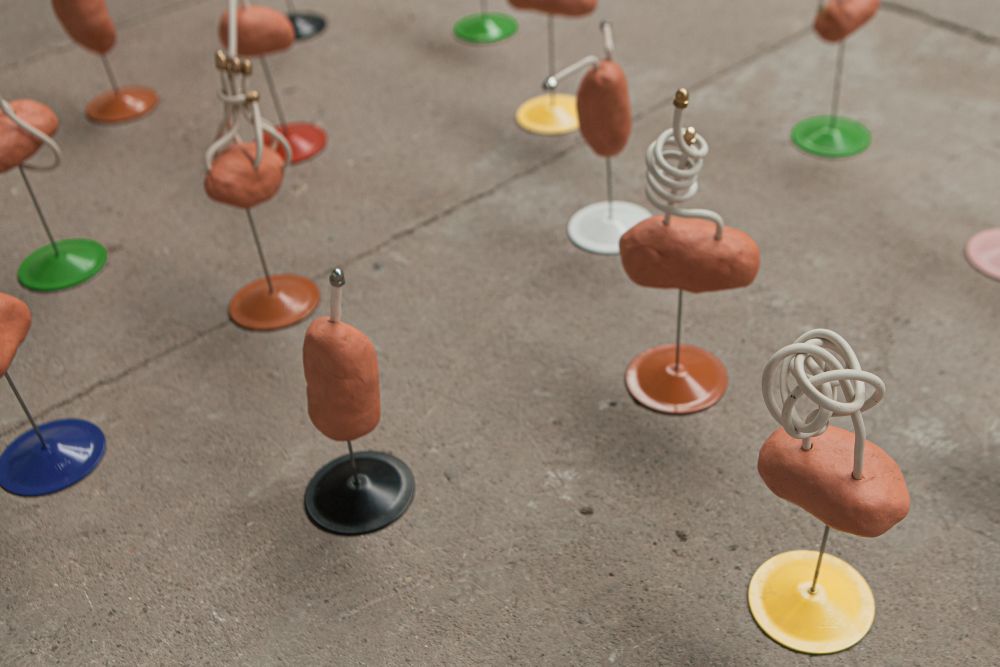

In this show, the sculpture group ”Basic pride II” consists of 20 single pieces of potato

sculptures and combining it with flag poles. Entangled, twisted, and pressed to each other,

or sticking through the potato, the poles stand for diverse nationalities and culture clashes

that come along with global unifications.

“Estonian Dream” is a video work that astonishes. There is a rawness in the video log format

and a naivety, sincerity, and obscurity in the main character – Texasgirly1979, an Estonian

woman who has lost her connection with her homeland and taken-on the American way of

life with a marriage and living in the USA. She is alienated from both the Estonian and

American cultural world. She carries out her life in a mode of nostalgia, going back to her

childhood songs, and has romanticised everyday goods that remind her of her youth. Her

manners and thoughts may seem laughable, but the video also calls upon empathy for

individuals who get disoriented in a globalised world and experience a nostalgic-homesick

loneliness, because of rootedness.

The three-channel approach is intriguing and conceptually appealing in Alexei Gordin‘s

video “If it disappears from here, it immediately appears somewhere else”, where he

rediscovers abandoned and forgotten architecture of past eras. This division to three

screens effectively gives a sensation of division of the space, time and the physical body,

which is also characteristic of a polarised psyche between the past, present, and future.

Images and architectural objects, collected in the video, lead a viewer to a journey through

the forgotten and ruined, pointing to the uncomfortable past we all share, and questioning its

influence on our future. Places documented in the video, remind us of something we would

rather forget as a mistake, but in another way, could be inviting and intriguing, such as

prohibited monuments that are stuck between time, cultures and memories.

The two dispatches of “Between the Past and the Cosmos I and II” paintings and the works

“Lights” and “Spring” depict a very Gordon-like societal portrait that spotlights the dramatic

distance between human reality and human imagination. The first two are partly inspired by

trips to Ida-Virumaa – the poorest part of Estonia, which is mostly populated by Russians

who migrated for work during the soviet era, but nowadays, time seems to have stopped

there. People have no work and no possibilities for development. In addition, a high rate of

alcoholism and drug addiction is common in this region, which is also reflected in the

demographic situation. Alexei says that he used metaphoric solutions to the problems of his

characters in imagining an alternative reality for them in cosmos, which signifies people’s

aspiration for ideal, harmonic life.

Evi Pärn‘s installation “The Corridor of Power” highlights a crucially important aspect of the

social structure in a post-occupational society in which the differences of historical

interpretations are a daily experience. This work criticises the institutional position of the

Estonian Art Museum, specifically the permanent exhibition about art and society in Estonia (1945–1991) where the historical contextualisation is displayed in Estonian and English, and

by this neglects the presence of Russian and Estonian-Russian citizens. Pärn creates an

archival corridor consisting of paper banners adding the Russian version of museum texts

and blurring the parts in Estonian and English to the edge of being illegible. The relation

between Russians and Estonians is complex and multilayered so an easy answer for a

solution can’t be given. It would be useful, however, to analyse the cultural past together, which could result in higher attentiveness and acceptance.