Artists: Inside Job (Ula Lucińska and Michał Knychaus)

Title: Breathing in the Shallows

Venue: eastcontemporary, Milan

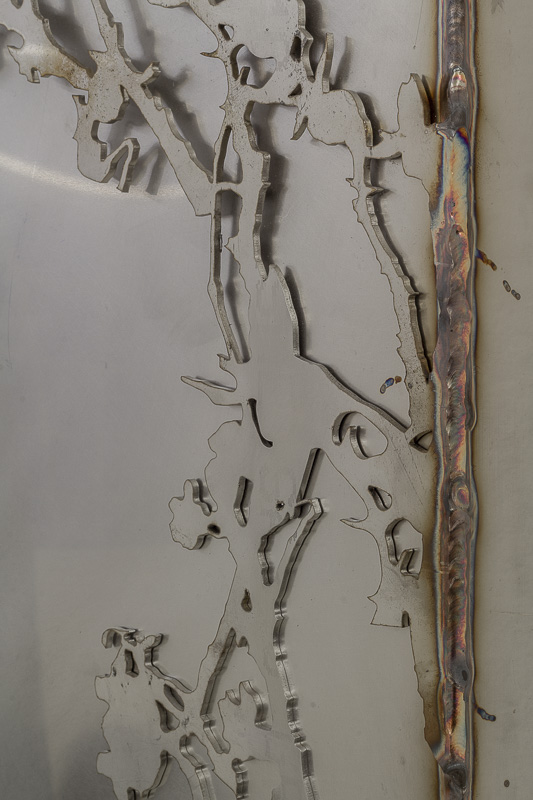

Breathing in the Shallows features a new body of works by Ula Lucińska (born 1992, Poland) and Michał Knychaus (born 1987, Poland), who work together as the Inside Job duo. The Inside Job’s practice is based on the use of different mediums and materials that lead to the creation of spatial installations and multi-layered environments emanating futuristic and post-apocalyptic scenarios. A research originating from the fields of science fiction, futurology and post-humanist theory is at the centre of this presentation focusing in particular on the phenomenon of matter’s transformation and the concept of the imagined afterlife of the objects.

Both graduated from the University of the Arts in Poznań, the artists have just completed their artistic residency at Rupert Residency in Vilnius and FUTURA in Prague, while this autumn they will have their first solo show in Paris at Lily Roberts. Furthermore, they were invited to exhibit during the 34th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana.

eastcontemporary

Agnieszka Fąferek and Julia Korzycka

Gaia’s Eyelid

-ev’n with us the breath

Of Science dims the mirror of our joy…[1]

Edgar Allan Poe

The cloudy water surface shivered, rippled by what might have been early-stage ctenophores. Pulsing slowly, their motion recalled the copious underwater dwellers of the building’s first flood. People tried to reclaim the entire area at the beginning of the century, yet the long rains of the following years eventually turned the mall into a broad, silent swamp. The sign over the main hall was pretty ironic, The New World. Thinking of the concrete that held the pressure of all those tons of water, of showcases now entirely blinded by lichens and albino creepers closing pillars in a deadly embrace, it was difficult to consider that pond as either entirely natural or artificial. Anyway, was that really a pond?

The opening was said to be somewhere in there, astride many conflicting indications stratified over time, which made it difficult to locate. The only element on which all the directions matched was its dual nature; the gateway was composed of two complementary openings, albeit no one had ever successfully guessed their spatial correlation. Even if one were found, it wouldn’t have given any clue as to the other’s position, nor about where to activate them.

Curious how, depending on the usage of an opening, many of the old languages had different words to define that very same concept. If space is a whole where everything is connected, how can one enter or exit from it? On a closer look, the fact that all notions of the world were outmoded at the time may have been the reason why all indications were so blurred. Back then, even the idea of a self-regulating system was viewed with criticism — as if the understanding of a planet as a single living organism was lacking in some evident form. The location of the gates was not the only vague knowledge, as everything related to their appearance was mere speculation, too. Regardless, they were expected to lie in some of the many evocative sites offered by this spontaneous temple. Nature’s design is always faultless. The two gates were thought to be specular and frontal for a long time, but, once again, this belief was part of an atavistic delusion. How can there be a double, if we are all part of one?

Sitting in front of spider-cracked glasses, sauntering between broken columns, I wandered for hours. I stood firmly under a Usnea-covered escalator, waiting for a sign, a glint, an unnatural puff of wind behind the shoulder. Listening to other parts of me would have only required a little attention, except that it had to be performed with a sense not yet fully developed. The fact that life has decided to mutate into separate lineages, deluding its supposedly smartest one into believing that diversity equals hierarchy, has undermined our perception of being a whole. An awareness that could have been increased by the portals which I was doing my best to sense, anywhere near that excess of primeval soup. Just one of the many things we learned too late from plants, motionless by their nature and therefore forced to evolve to survive problems. Despite trying to keep this image in mind, I still couldn’t help but wander tirelessly back and forth through the abandoned building as the sun moved just as relentlessly.

The overlapping of the muggy atmosphere inside that worldly court—its name turned out not to be all that inappropriate—and the setting of the sun outside created a suffocating gloom. Calling it a day was a quite endured choice, yet the only one left because of the approaching darkness. My first attempt had not been more successful than those of many others before me, after all. I decided to freshen up before starting to build a camp and immersed one hand in the pond; under the surface, its water was surprisingly clear. Then the wonder emerged to overflow; I couldn’t see my hand anymore.

Waving my phantom limb between a few tadpoles, I admired the motion generated by what appeared to be just a void. In the moment of surrender, the lucid dream was complete. I got closer to the surface; underneath, the rainwater was abundant in opaline plants wiggling around, trying to grasp anything that moved with their tiny mouths. While floating weightlessly over to the surface, I imagined myself becoming something else.

The light flickered as I entered.

[1] Edgar Allan Poe, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, 1829

Zoë de Luca

The exhibition was organized with the support of the of the Consulate General of Poland in Milan, Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Polish Institute in Rome.