Artist: Joanna Piotrowska

Title: Implicit Lives

Venue: MADRAGOA, Lisbon

Smultronstället is the original Swedish title of Ingmar Bergman’s famous film Wild Strawberries (1957). Smultronstället, which literally translates to “the wild strawberries patch,” idiomatically signifies “a hidden gem of a place” (according to Wikipedia). The word defines a special place that is close to one’s heart, where one feels at ease and comfortable, like a childhood home, and not widely known. It is a secret place, akin to the idea that everyone has their own place to pick strawberries, which they selfishly share with no one.

In Bergman’s film, the strawberry glade is the pivot around which the narrative unfolds; it represents the viewpoint from which the elderly protagonist casts a glance at his past to take stock of his existence. In the same way as a Proustian madeleine, that place triggers a sequence of images and episodes of lived life to surface in the old man’s mind, which by their vividness make the present reality dissolve. From a physical place, the strawberry patch becomes a device for time travel, piercing the space-time continuum and allowing memories to emerge in fragments, frames, and brief epiphanies. The narrative shows that past and present are not strung together in a sequence but are inextricably intertwined within the character’s consciousness.

For her series of photographs that began with the exhibition Frantic (2016-2022), Joanna Piotrowska invited people to construct small shelters to inhabit within their own domestic walls, built from objects at hand, such as chairs, tables, blankets, and curtains. The outcome of the project is a gallery of portraits of these shelter dwellers, posing within their precarious inhabitable assemblages—cozy places to isolate themselves from the world, to hide—that are reminiscent of huts built for play by children.

In the exhibition Implicit Lives, a similar intimate dimension, achieved with elements of domestic furniture, triggers a journey through time. Black-and-white photographs depicting men and (more often) women, caught in mutual, enigmatic, and suspended gestures, analogous to the Frowst series (2013-2014), are here embedded in a domestic landscape.

Printed on fabric and installed as if it were a curtain, mounted within a soft fabric frame or framed in veneer panels that extend along the wall, or in freestanding screens that subdivide the space, the works create a continuum between the atmosphere emanating from the pictures and the actual physical space. The selected visual elements, fabric patterns, and veneer surfaces, with their vintage flavor veiled with a sense of nostalgia, can evoke to today’s adults the domestic interiors of a home they inhabited during childhood or adolescence. In particular, the mottled pattern of the veneer grain brings one back to the dimension of childhood for another reason as well.

Who as a child, on afternoons of gilded boredom, has not practiced recognizing in the wood grain of furniture or parquet floors the features of a face? Anything but a child’s occupation, the phenomenon is called pareidolia and is described by Leonardo in his A Treatise on Painting. It is a process of interpreting real but incomplete visual stimuli in a way that leads to the perception of meaningful forms, such as human faces or objects where there are none (stains on walls, clouds, shadows). An innate propensity that evolved for the survival of the species due to our prehistoric ancestors’ need to recognize a possible predator, however well camouflaged, pareidolia is a congenital faculty, but it is also the product of previous experiences that allow us to see what we want to see.

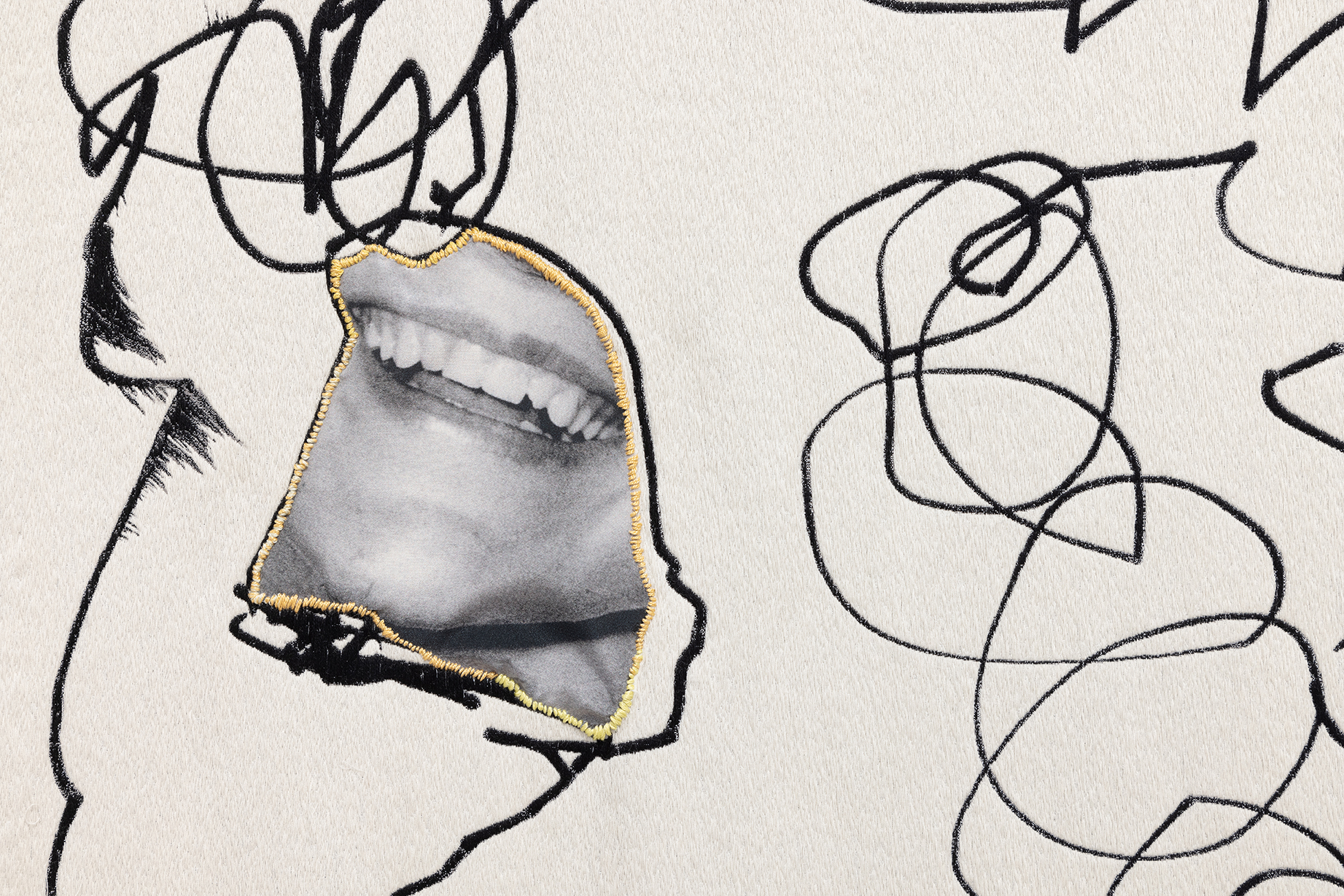

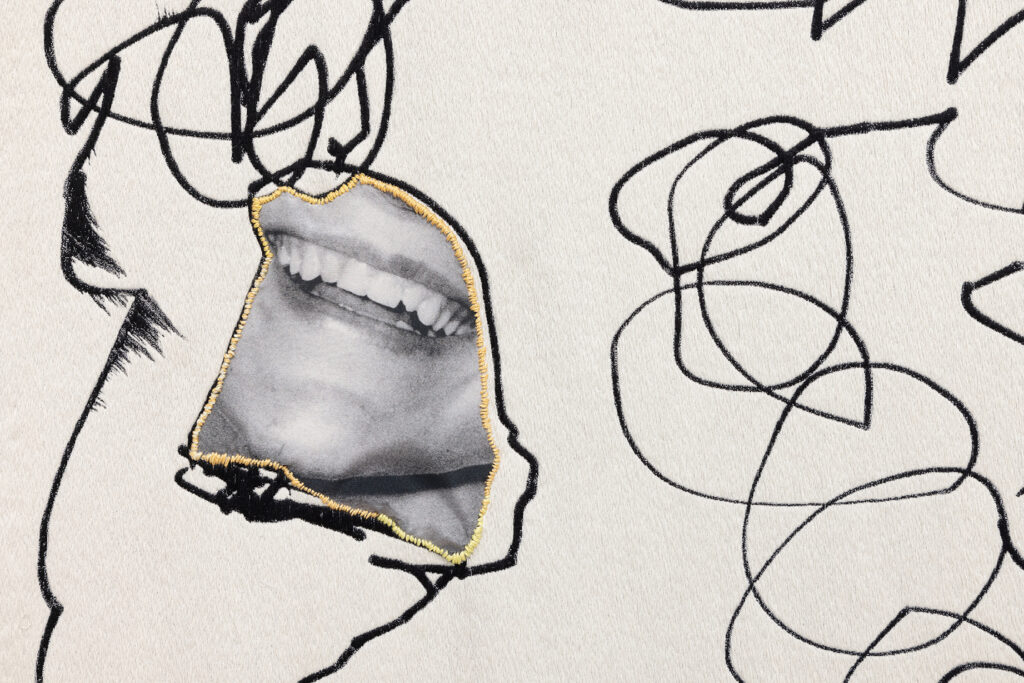

The oneiric squiggles of faux wood echo in the childhood drawing, elaborated by the artist from a group of drawings executed by herself, her sister, and cousins when they were children, which became the weave of a tapestry. The erratic black line, thin or thick, is a seismograph that records gestures and moods, an automatic or rather pre-verbal, unconscious writing.

The word “implicit” in the exhibition title refers to a certain type of unconscious memory. “In psychology, implicit memory is acquired and used unconsciously, and can affect thoughts and behaviors. One of its most common forms is procedural memory, which allows people to perform certain tasks without conscious awareness of these previous experiences; for example, remembering how to tie one’s shoes or ride a bicycle without consciously thinking about those activities” (according to the definition in Wikipedia). Among the effects of implicit memory is the illusion-of-truth effect: “subjects are more likely to rate as true those statements that they have already heard, regardless of their truthfulness. (…) The illusion-of-truth effect states that a person is more likely to believe a familiar statement than an unfamiliar one.”

The image one recognizes in the wood grain clearly does not exist, and yet one continues to see it clearly.

The photographs, subjects, materials, and surfaces used by Joanna Piotrowska in the exhibition reconstruct a personal, evocative rather than objective, universe. It feels familiar and stimulates observers to project themselves into it. Everyone can recognize in it an echo of their own lived experience and the nostalgia that the past can evoke. At the same time, the photographs and the display state that it is just a reconstruction—an illusion of truth—the checkmate of any attempt to reconstitute the past, in the present time, in an unambiguous way. Recollection can only proceed by fragments, epiphanies, surfaces, by isolating details or gestures, mimicking the mechanism of memory or dreaming—moreover evoked by the closed eyes, the lying position, of the abandoned limbs of some of the portrayed figures.

The reconfiguration of a personal place—physical and metaphorical—in a montage that mimics the unpredictability and selectivity of memory is emphasized by the use of collage. On recently shot photographs, the artist superimposes fragments of photographs belonging to her family history, including details of her mother’s face. The synchronic presence of past and present characterizes collage, a technique that also eschews complete control of the self.

The self is also bracketed in the photograph depicting two brothers printed on fabric: it is the outcome of the jamming of the roll of film, which instead of running has captured the image several times in the same portion of film. Instead of in sequence, the gestures are superimposed into a single image of intangible substance, made up only of shadows. The picture with its unintentional layering falls within those perceptual phenomena invisible to the eye, but which the photographic lens is able to record thanks to what Walter Benjamin called the optical unconscious.

A phantasmagorical presence—fruit this time of collage—is also found in another photograph in which the silhouette of a female figure is replaced by her veneer outline. It seems that the woman dematerialized to teleport elsewhere, while her body was replaced by a two-dimensional surface.

This ghostly dimension evokes a common belief at the time of the origin of photography. As Nadar wittily recalled: “According to Balzac’s theory, all physical bodies are made up entirely of layers of ghostlike images, an infinite number of leaflike skins laid one on top of the other. Since Balzac believed man was incapable of making something material from an apparition, from something impalpable—that is, creating something from nothing—he concluded that every time someone had his photograph taken, one of the spectral layers was removed from the body and transferred to the photograph. Repeated exposures entailed the unavoidable loss of subsequent ghostly layers, that is, the very essence of life.”

A hint of this power attributed to photography (almost like an involuntary memory) echoes in the words of Susan Sontag, when in her 1977 On Photography, she stated “…a photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.”

In the exhibition, epidermis, dresses, textiles, film, veneer, and the grain of photographic paper are all layers that hold the imprint of a past. They are a number of leaflike skins that envelop the bright gem of memories and at the same time draw the perimeter of a warm physical place. Your patch for picking wild strawberries may also be there, in the hiding place behind the curtain, or among the pansies printed on a dress.