Artists: Dominika Trapp, Julia Gryboś & Barbora Zentková

Title: Soilmates

Curator: Jan Zálešák

Photos: Michal Czanderle, Ondřej Polák, Barnabás Neogrády-Kiss, Benedek Regős

Venue: Hunt Kastner, Prague

Hunt Kastner is pleased to present the exhibition Soilmates, a collaborative installation featuring the current work of Dominika Trapp and the artist duo Barbora Zentková & Julia Gryboś. The exhibition’s title plays with the possibility of kinship that is already established on an “elemental” (material or fabric) level. This pre-conceptual proximity, anchored in the material plane of the work and foreshadowed by the title of the exhibition, really came to the fore in the process of installation, resulting in an unexpectedly impressive impression of unity and dialogicality. The exhibition consists of several bodies of work; however, in the accompanying text, we will focus in greater detail on only a selection.

Julia Gryboś and Barbora Zentková are featuring here paintings from the series Undertones Between Serpentines. Two of the works, located in the entrance room of the gallery, were entered a year ago for the eponymous exhibition in Bratislava’s Nová Cvernovka Gallery. For Soilmates, Gryboś and Zentková prepared a new diptych, in which they retained the compositional/constructional principle of layering and stitching (combined with the compression of the material) of thousands of strips of hand-torn textiles. The strips of fabric, if they do not already have the intended shade, are dyed by the artists before being inserted into the mass of the selected segment of the painting – in the earlier pieces mainly with earthy shades of brown and ochre, and in the new pair with a different palette of predominantly grey and blue tones. Both diptychs then enter into a spatial and visual interaction in the installation with broad strips of gauze dyed with natural pigments. The artists have worked with this element in the past, for example as free-hanging “curtains” in the exhibition Bone Tone Shelf Self (2022) at the Kurzor Gallery in Prague. Now, they apply the gauze directly to the gallery wall using a natural binder, shifting its appearance towards a site-specific mural.

The way in which the substances are stacked in the paintings of the Undertones Between Serpentines series evokes Bratton’s metaphor of the “stack” as a planetary infrastructure of layers incorporating both natural and cultural elements. Zentková and Gryboś mainly work with textiles that have reached the end of their life cycle and thus enter the picture equipped not only with specific material qualities, but also with a specific history involving their place of origin and modes of use. In this case, upcycling is associated with a radical functional transformation. The fabrics lose their original purpose, we do not see their surface, but only the layered cut (or “tear”) of the material, which is thus reduced to a nerve line in the frontal view. In a close proximity to more and more such lines, the textile nevertheless retains its material quality, mass, and weight. This opens up space for the question of whether to think of these works as paintings or rather as sculptures or low reliefs.

The works from the Undertones Between Serpentines series can be seen as representations (images), but also as literal materializations of processes of sedimentation, gradual settling, and layering. They can thus resemble a bedrock cross-section or a soil profile. Looking beneath the surface of the earth corresponds to looking into the past: where the earth opens up before us (or is forcibly cut into), we see layers that have been formed over long periods of time by the sedimentation of inorganic materials transported to the site from elsewhere by erosion, or layers formed by the decay and gradual transformation of organic materials. In another type of association, these images evoke cuts through body tissues. Like the cuts through soil or rock, the cuts through our bodies are most often the products of “expert knowledge” and are presented to us laymen as images of mysterious, unexplored territories. We need not necessarily begin to discuss the connotations of surrealist imagery and metaphor, but it is certainly interesting to consider them. Consider, for example, decals or rubbings, which often evoke glimpses into the inhuman bowels of nature. The imprints of color or pencil hatching open gates or portals through which one may not only enter the human unconscious, but also simply step beyond the human.

Similar portals or “gates between dimensions” also represented by traps, which Dominika Trapp explores in her paintings and drawings. A trap set in the landscape looks at first glance like something that can easily be interpreted in a binary opposition of the natural and the cultural. On closer inspection, however, this binary becomes complicated, e.g., by the very fact that the successful trap is the result of a particular empathy or mimicry aimed at merging with the umwelt of the animal to be trapped or outright killed. In the tragic act of entrapment (killing), which Trapp nevertheless never captures and thus remains present in the paintings as potentiality, two seemingly incompatible perspectives collapse into each other.

Trapp became intensively involved in the subject of traps about three years ago, when she accepted, together with Ádám Albert and Krisztián Kristóf, an offer to undertake artistic research in the collections of the Budapest Ethnographic Museum (Néprajzi Múzeum). The commission resulted in their joint exhibition Suspension of Disbelief (2024), in which Trapp presented a series of her own works interpreting selected artifacts alongside selected objects from the collection. Trapp’s interest in traps was certainly related to her enduring interest in manifestations of power and the formation of hierarchies at the level of social structures and personal relationships. At the same time, however, it was also motivated by the morphology, material qualities and poetic potential of the artifacts themselves, often very modest and at the same time curious objects, escaping the anthropocentric logic of craft with their orientation towards the end animal “user.”

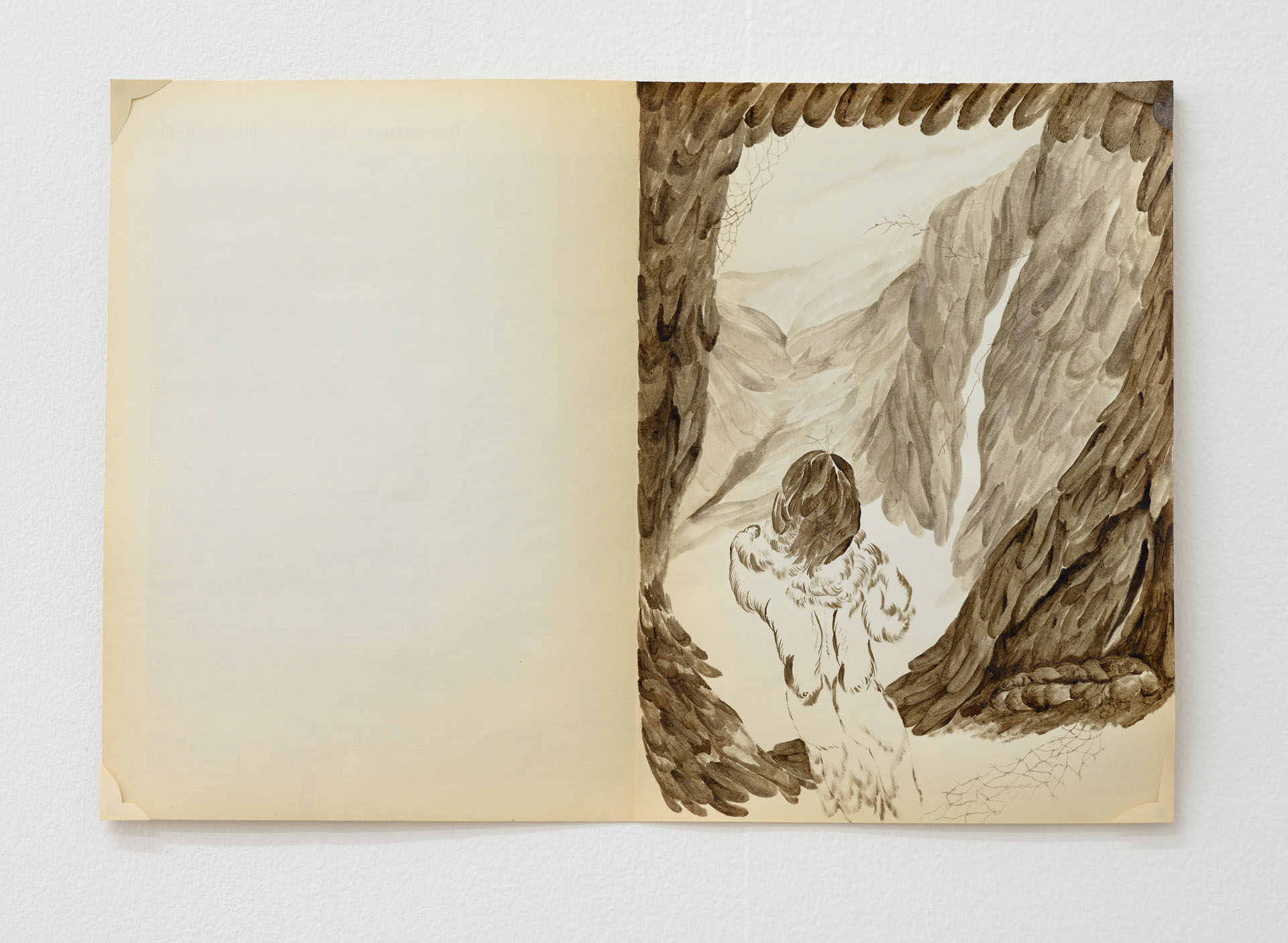

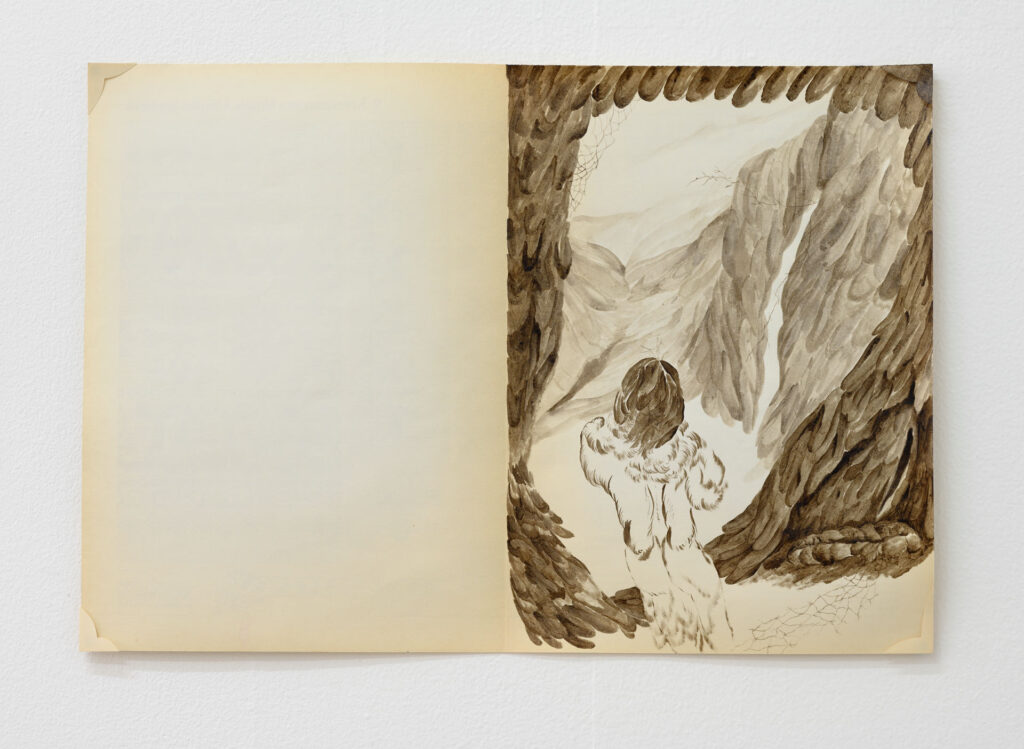

In the early stage of intense engagement with the theme of traps, a series of works on paper were created, which are presented in the Soilmates exhibition in the last room. This a series of ink drawings “…like a ring, sliding shut on some quick thing,” Trapp first presented in 2023 in an exhibition at Budapest’s Kisterem Gallery. In these works, we see several simple traps – snares – set on what appear to be branches and sturdy leaves or tendrils, which also ripple across the formats like the edge of a curtain or drape. Some of these snares (which also look insistently like nooses) already contain dangling bait. The undulations present in the “structural elements” of the traps seem both part of the material and a kind of overarching principle organizing the action in the drawings. Strands of grass, fibers, or hair are woven into thicker formations, braids, and knots. These, in turn, unravel elsewhere, subject to entropy, which can be temporarily prevented by adding a knot, or by clamping it with a clamp or clip, all without the apparent presence of the agent of these interventions.

In addition to these works on paper, Trapp also presents a trio of canvases created specifically for the Soilmates exhibition. These paintings are based on motifs Trapp developed in a series of works on paper presented in Budapest as part of the group exhibition On Violence (2023). These motifs are not set in a clearly recognizable setting or context and retain a certain semantic openness, yet, at the same time, they are specific enough to represent traps formed again by the braiding of different threads. Traps are articulated here as “temporary infrastructures” created by interconnecting and linking sub-elements into more complex relationships. The inevitable presence of violence, whether symbolic or physical, is also problematized by how we see traps: as something tempting, as a possibility, as an escape route. Isn’t the strange calm that the works exude, despite the many particular disturbing elements, a sign that we have already smelled the bait?