Artists: Øleg&Kaśka

Title: The Food of Life

Curator: Eva Slabá

Man was created of the Earth, and lives by virtue of the Aire; for there is in the Aire a secret food of life, which in the night we call dew; and in the day rarified water, whose invisible, congealed spirit is better than the whole Earth. (Michał Sędziwój)

Although the letter O and the number 8 are just arbitrary symbols for oxygen, they represent a graceful symbolic harmony between nature and human thought. We perceive both the closed circle and the horizontal eight as symbols of eternal cycle and wholeness, whether it be inhalation and exhalation, burning or photosynthesis, growth or decay. This life-giving substance – the “food of life” – was described as a component of air by the Polish scholar Michał Sędziwój in his text Novum Lumen Chymicum (1604). His pioneering findings on the chemical origin of oxygen served more than a century later to identify this essential element. And it is no surprise that Sędziwój was staying at the Prague court of Rudolf II at the time, which was (and still is) often mentioned in connection with alchemical explorations.

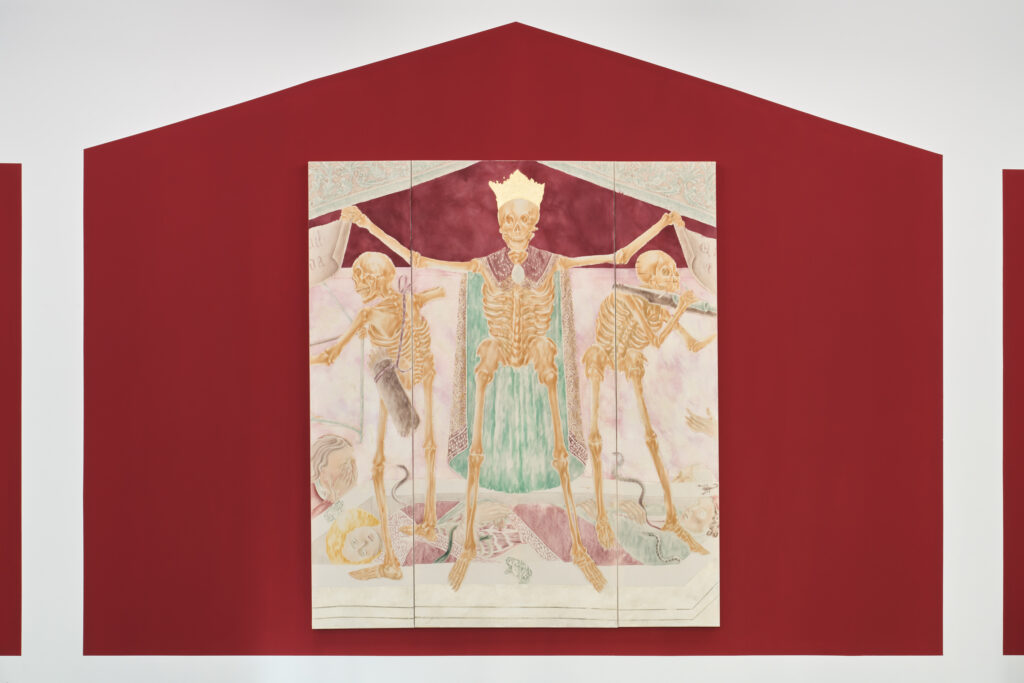

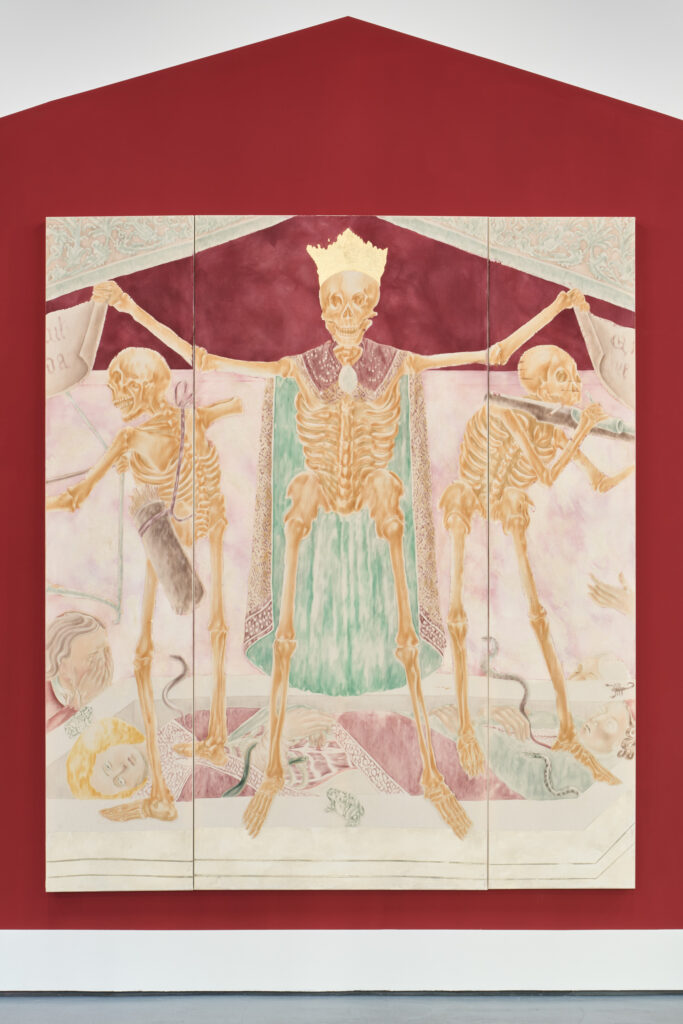

Øleg&Kaśka borrow the idea of “food of life” for their macabre exhibition at the Polansky Gallery, in which they take a playful approach to the dynamics of human life. Against the backdrop of a warm, brown-red banquet hall, they present their paintings and authorially adjusted drawings, as well as papier mâché busts. Unlike the linear principle of memento mori, which encourages reflection on the transience and finitude of earthly joys, Øleg&Kaśka reflect more on the cyclical nature of all living things in the concept of eternal return by Romanian philosopher Mircea Eliade. His distinction between profane time and sacred time points to the role of myth. Myth is not just a story of the past, but an active way in which individuals or societies organize their relationship to the present. Myth allows us to reconnect with sacred time through archetypal events and free ourselves from the anxiety of the irreversibility of the passing of time. The gradual awakening (similar to the burial of winter or New Year’s celebrations) is reflected in the exhibition not only in the choice of themes, but also in their formal handling.

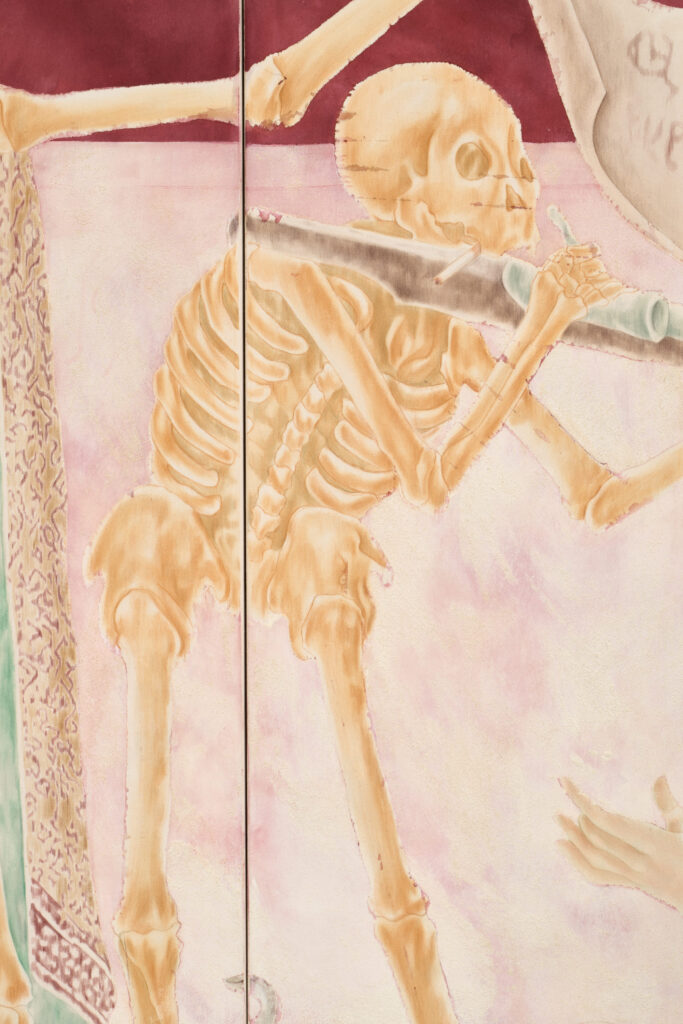

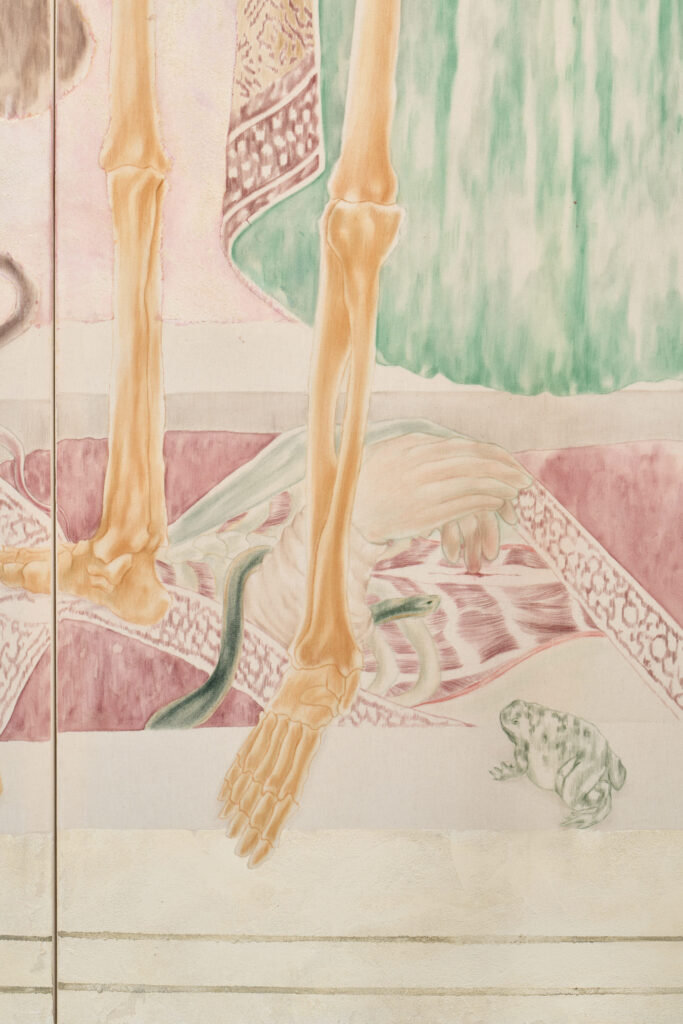

The Food of Life triptych deliberately resembles a restored Italian fresco. The artists achieve this effect by first sewing together different parts of the canvas, then layering acrylic, watercolor, pastels, and sand gesso, and finally removing these layers with sandpaper. Similar to the restoration of wall paintings, we find places on Øleg&Kaśka’s canvas that disappear and reappear, almost as if they were breathing pores or permeable fabric emphasizing the tension between history and memory and their possible manipulation. From the soil loosened by the remains of all that was, there emerges not a funeral disorder but a hermetic pool of knowledge that the soil was, is, and will be one of the sources of life. Contrary to custom, the authors thus place the end right at the beginning.

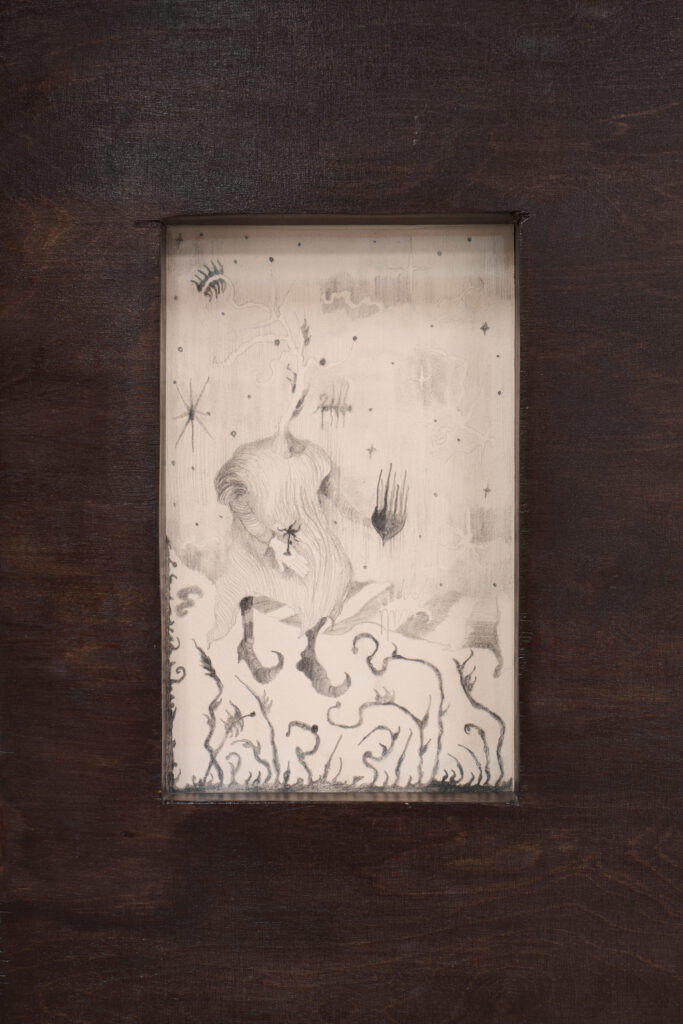

The authors refer to traditional paradigms – the position of human beings above nature, the idea of linear development, and the hierarchical structure of society – in their other works as well. The diptych The Dew of Night depicts a hunting scene. The azure sky, saturated with the “food of life,” is replaced by a murmuring omen, which makes itself known through the spears of rays that descend from it and, already in their transformed form, spill the blood from the squire’s torso with well-aimed blows. The theme of court life and its political intrigues is further developed through sculptures of heads, inspired by the so-called Wawel Heads (circa 1535) by Sebastian Tauerbach, which, although silent, still gaze down from the coffered ceiling on the events in the Throne Room of the Royal Castle in Krakow. Whether they were allegories or astrological symbols, they can be considered portraits of representatives of various classes and social groups, whose significance the artists shift from the role of powerless witnesses to that of direct participants in events, now with their gaze raised. The third canvas in the exhibition, Chess Player, an allusion to Albert Pictor’s medieval painting Death Playing Chess (1480), connects the immortal and his bones with chess games, whose design is also reflected in the artist’s frames of the drawings. All of this comes together here in a clear message – a reminder of events and structural struggles that are repeated regardless of the passage of time and experience gained.

The return of the dead is a common theme in works of art. In his magical realist novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez refers to memory and the cyclical nature of individual destinies, as does Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk. For Tokarczuk, however, this leads to something else – a sensitivity to connections (from her speech The Tender Narrator, delivered in 2019 when she received the aforementioned award). It is a type of storytelling and perception of the world that is more than just a causal chain of events. For her, this tenderness is a call for a new type of narrator who does not divide the whole into separate parts, but seeks connections through new structures and myths. In her later essay, she concretizes this idea under the term Ognosia – a process that attempts to organize objects, situations, and phenomena into a higher, interdependent meaning. Linear stories or mental models are no longer sufficient to capture the complexity of the contemporary world; it is necessary to take into account the multi-organism network of relationships between all living and non-living things, even if these connections are not yet known to us, in contrast to the traditional model of the isolated “man-narrator-ruler.” Instead of a third-person narrator, we find a panoptic narrator whose mode is pluralistic and expansive. Øleg&Kaśka adopt this perspective when, through their works, they freely flow through time, space, reality, and imagination, reminding us of the mutual permeability between the world around us and the human being itself. They allow us to breathe in the purest essences of the “food of life,” which saturates the air just as Ognosia saturates the environment they have created.