Artist: Maja Štefančíková

Title: Spatial Sketches

Performers: Silvia Bakočková, Viktória Malá, Nela Rusková

Curator: Eliška Mazalanová

Venue: Gallery SUMEC, Bratislava

Production: Ľuboš Lehocký, Gallery SUMEC

Technical support: Matej Gavula

Photos: Adam Šakový

Before dust was rationally and scientifically explored, broken down by knowledge into ever smaller

particles, and revealed to contain an entire universe of parallel microworlds, it was imagined as the

smallest possible entity, the most elementary unit of matter. It represented the boundary between

the visible and the invisible. Dust became a symbol of nothingness and futility. It refers to the limits

of the physical world, to its finitude, which for those yearning for eternal life generated contempt for

corporeality. Dust is melancholic—it points to decay, ruin, and oblivion, and can just as well be a

symbol of a vanishing, self-destructive civilization. From the perspective of today’s knowledge,

however, it appears to be extraordinarily vital, permanent, and omnipresent. There is the fascinating

and poetic cosmic dust; there is the feared and mandatorily monitored particulate matter in the air;

and there is household dust, which must be constantly eliminated in the name of hygiene and order.

Dirt is either overlooked or irritating. Why does something appear dirty to us and evoke disgust?

Why does it compel us toward certain kinds of behavior? Dirt and dust activate something

instinctual, rational, and ritualistic within us at the same time; they are exceptionally rich in meaning

and capable of narration. Above all, the categories of dirt and cleanliness, in their opposition, can

speak eloquently about social oppression. For example, the oppression of women—as well as men

and sexual minorities—through ideals of moral purity, or the oppression and even murder of people

of other ethnicities or the sick in the name of an ideology of racial purity. Even seemingly innocent

physical cleanliness, order, and hygiene—and with them cleaning and care—are sources of

inequality: they have traditionally been, and still are, the lot of women, the socially disadvantaged,

and ethnically marginalized groups, as invisible and undervalued labor. Owing to the relentlessness

of dust and dirt, this is labor without lasting results or satisfaction—endless and monotonous work

that exhausts rather than stimulates ingenuity and creativity.

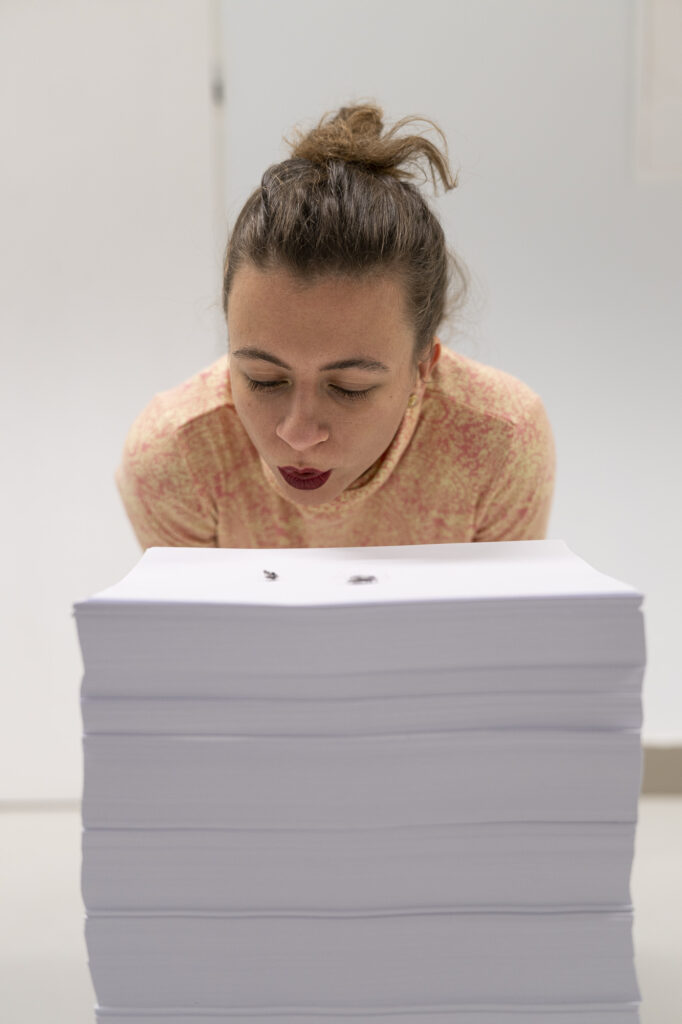

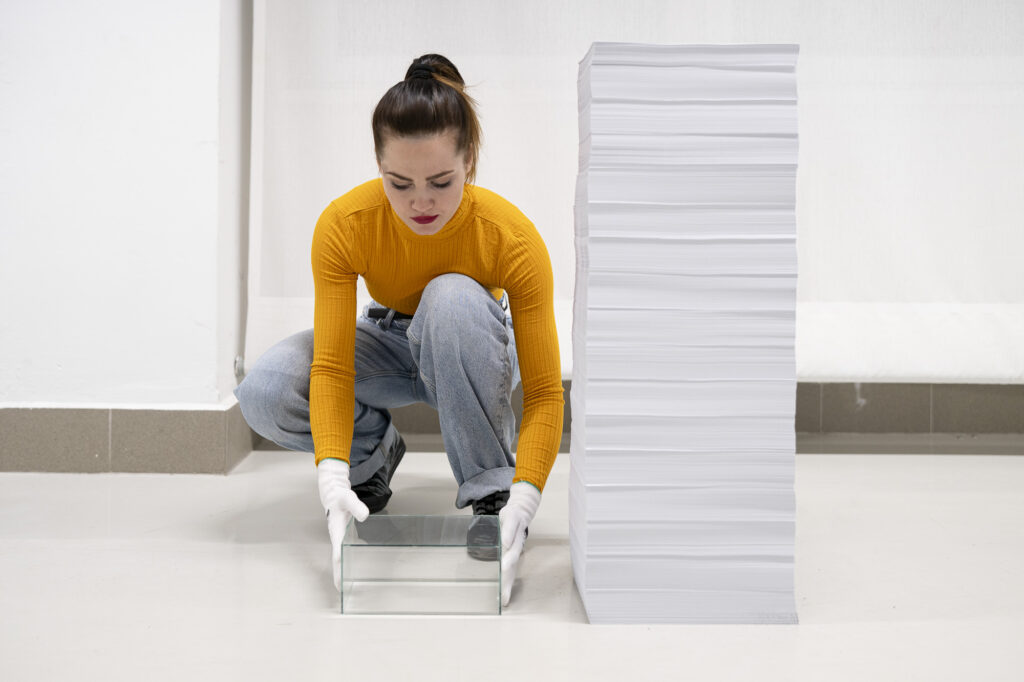

Although Maja Štefančíková’s Spatial Sketches may at first glance give the impression of emptiness

and immutability, they are based on activity, on systematic and cyclical action—on the regular

cleaning of the exhibition space. They take the form of a performative action: cleaning, during which

a performative intelligent vacuum cleaner precisely cleans the gallery. The dust removed from the

space is then exhibited on white plinths—large stacks of white paper resembling sketchbooks ready

to capture the trace of the space. Dirt, originally unwanted and destined for removal, thus

paradoxically becomes the material of the exhibition, transforming into a visible trace of activity.

Spatial Sketches are about dirt and cleaning, yet they do not refer only to the aforementioned

feminist tradition and the question of labor; they also comment on the field of art itself, the gallery

space, exhibition-making, creation, and self-realization. The work engages with an empty (yet

meaning-laden) gallery space that is clean, universal, modern, and purposefully rational. The school

Gallery Sumec, which strives to approach this ideal, appears in sharp contrast to its

surroundings—the school and its everyday functioning, with its daily work, maintenance, and

practical constraints. Originally conceived for the plusminusnula gallery in Žilina, the project, in contrast to reality—here also the reality of a school—reveals the invisible labor of care that underlies

gallery cleanliness.