The Marinko Sudac Collection based in Zagreb encompasses a large number of artworks of progressive Avant-Garde, Neo-Avant-Garde, and Post-Avant-Garde art, including morphologically and conceptually similar artistic developments, as well as various practices of experimental art across Europe and beyond from the beginning of the 20th century until the fall of the Berlin Wall. At the occasion of the exhibition Non-Aligned Modernity. Eastern-European Art and Archives from the Marinko Sudac Collection presented in FM Center for Contemporary Art, Milan, the collector talked to us about his background, theories on collecting and the Museum of Avant-Garde.

What is your background and when did you get in close contact with art?

It is impossible to pinpoint a moment which ignited the collector’s urge in me. Everything I know about art, I discovered through my own research. But this is not what matters now, as much as the realisation that art has become my everyday life – it gave me direction and enabled me to recognize its message. Through the art of early Modernism, firstly through Croatian artists, I began to realise that there is an entire scope of painting which left the traditional means of painting, I saw that there are deviations from figurative towards abstraction, and that some dynamic changes happened. At that time, I did not entirely understand it outside of that general, formal, art knowledge. Even now I cannot specify which specific artwork was the first one I wanted to have for myself. But I do remember that in the 80s I visited exhibitions in Zagreb where I met Račić, Kraljević, Bečić, Vidović, etc. including the Constructivist composition by Josip Seissel. Now I know that it was not the iconography of these paintings – I was more interested in the concept of changing the aesthetic principles of all these paintings in the realm of art. It was my first encounter with contextualising art. I was inadvertently drawn into these phenomena of art, and it lasts until this day. My collecting of one type of art could not have been possible without the encounter with the aforementioned painting of the Croatian Modern. Some incredible tautology was hidden behind all of that.

When, why and what did you start collecting?

I had created my first collection from the works of Modernist painters, but I quickly drifted away from that, foremost because I was not content with that imposed formal aestheticism which is very easy to understand, which does not have the potential of deepening the understanding of the context of social relationships. This is why I reached for that art in which artists in their actions take in regard certain social consequences, in which the excess is built as a foundation for further creation. If the entire 20th c. was loaded with political, technological, war, national turmoil, then the excesses of the Avant-Garde artists were a target of all political systems. This is the art that I started to research, and then to collect. In Croatia, there was this sort of hybrid art, that of a set bourgeois Modernism and local folk intimacy. This art had to be abandoned, mostly because the relationship between artists and the very act of creation had changed, as well as the artists’ relationship with society. When I say this, I must mention that this is for sure, in Croatian art, seen most radically in the work of Ivo Gattin. It is precisely due to this hard to notice changes that I started to build my relationship with the historical Avant-Gardes, as well as look for the connections with the artistic practices of the 1970s and beyond. Not even now, while I’m thinking about this question, I cannot figure out how the Avant-Garde artists, with their experiment, managed to create such interdisciplinary art and how they succeed in placing their socio-political engagement into artworks. I think that this intervention by Avant-Garde artist, as opposed to the Modernists who sought only autonomy in a given political society, is a great accomplishment of the 20th c.

The core of your collection can be defined as Eastern European neo-avant-garde. But we are also interested how you make particular choices. How do you select pieces for your collection and do you work with advisers/experts?

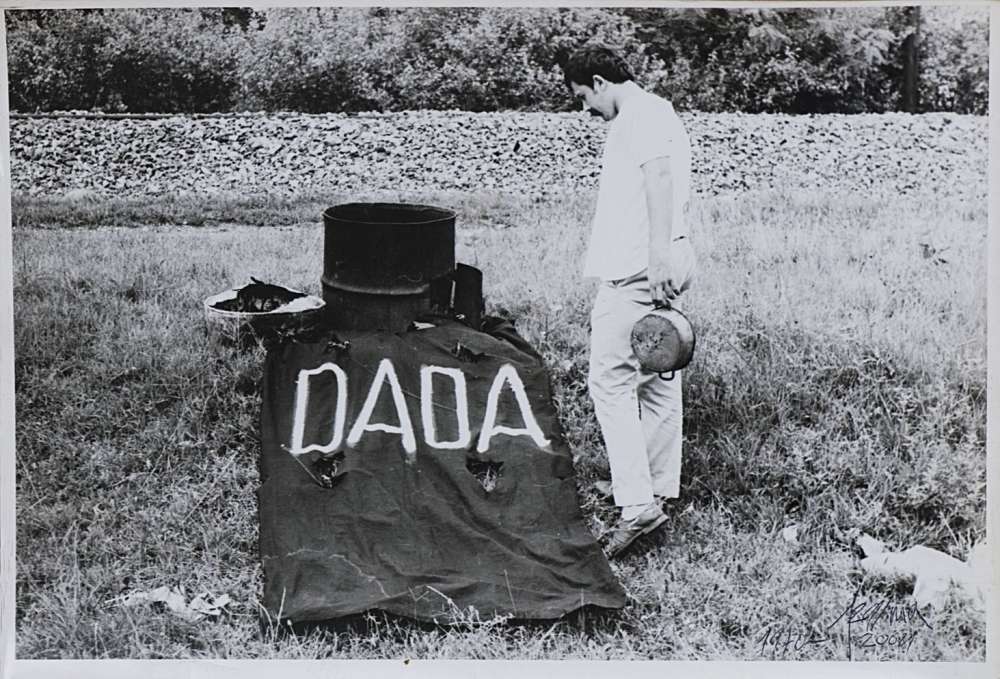

The core material of my collection is the art of Eastern Europe, the art of the first Avant-Garde and its entire legacy, up until the fall of the Berlin Wall. But I must clarify how to understand this determinant more precisely – the art of Eastern Europe after the Second World War, or how to find the points of contact with the interbellum period. If Dadaism was created in specific cultural-political circumstances of the First World War, which was at its core an imperialist war that redistributed the might of the major powers, then Dadaism must be understood as an excess, abandoning of the bourgeois lifestyle, but also art, which was based on God discourse, homeland, and family. Those three ideals of the bourgeois civil society caused the Great War which made the fundamental East/West divide. However, if we follow the line in which the “language of art”, created in the time of Russian Avant-Garde, moved and how it headed towards the West, then this political divide on the East and the West becomes relativized. Why am I mentioning this? It is to point to the fact that a great number of intellectuals, poets from Romania, Russian revolutionaries, then connected to Lenin and the utopia of the Bolshevik revolution, travelled to Zurich, the centre of bourgeois habitude, the city filled with cabarets, inviolable bourgeois area to fulfil ones free time. There they met, in a cabaret, Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara, a Romanian poet. They created a fundamental change, they attacked all the depleted values in the First World War – the bourgeois civil norms, and they destroy that discourse. This sudden inroad, the cultural diversion of the artists from the East, is an event with tremendous consequences for this which we today try to confine as Eastern-European art or Eastern-European Avant-Garde. In my way of collecting documents, paintings, collages, and other material of the artists of the “East”, I am trying to erase this division which was inherited in the redistribution of might after the Second World War on Yalta. Through an expert insight in my collection, I claim that the Eastern discourse is also the Western one, and that my collection is “proof” of this stance. This apparent controversy is, for now, my personal stance for which there will be enough material for the experts to either confirm or deny, but the basic answer is this – the East and the West are only narrow geographical determinants, and the language of art on both sides is singular. My answer might be too broad, but I am simply trying to find a scale in the widely-set framework of understanding the Neo-Avant-Garde artistic phenomena in the Eastern part of Europe, so we could together come to a single model of comprehending my collection in the context of the total historical legacy of the 20th c. Avant-Garde.

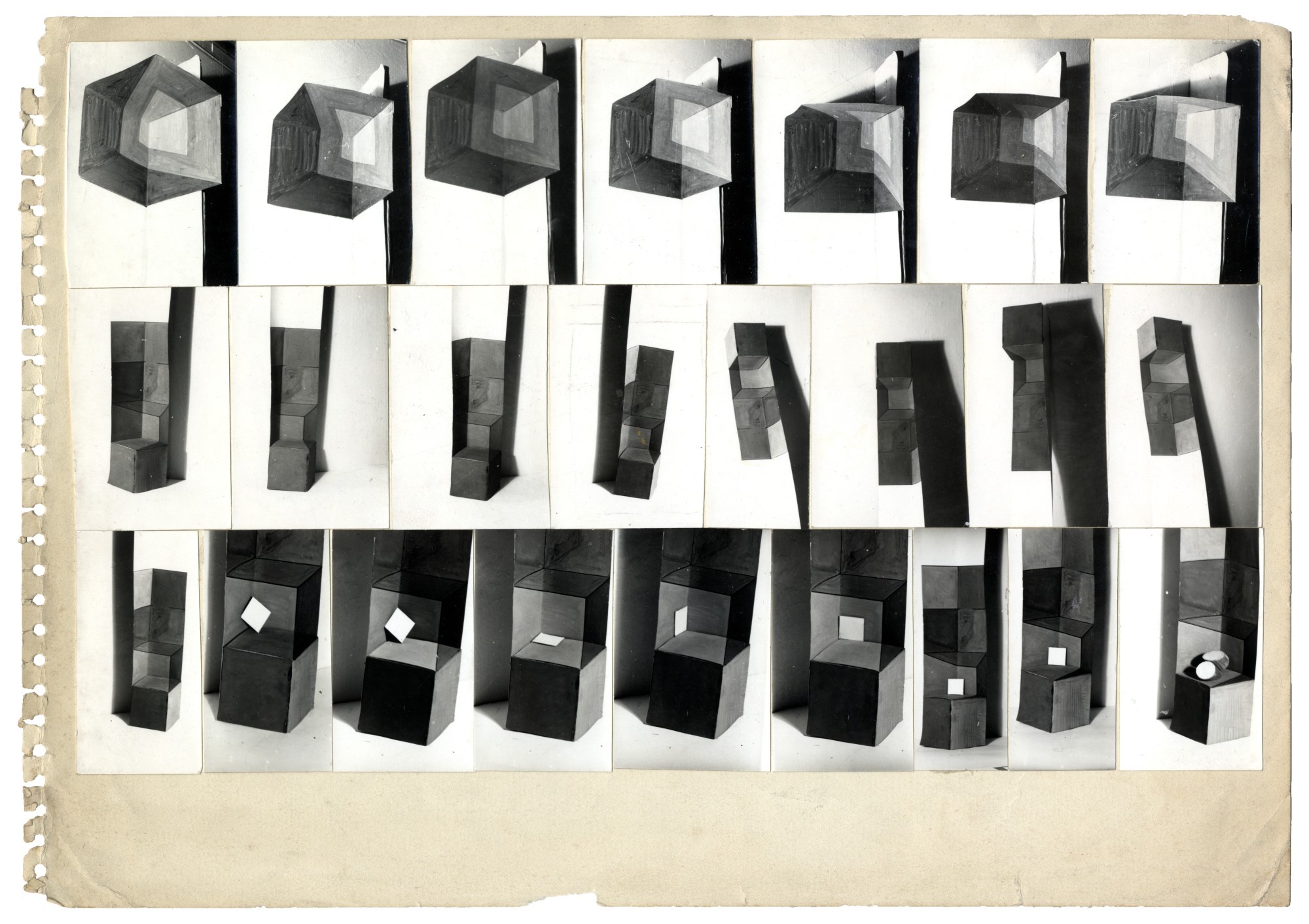

The title of the exhibition presented in Milano is: Non-Aligned modernity. Eastern-European Art and Archives from Marinko Sudac Collection. What is the nature of these archives and how do you make them accessible for researchers interested in this period?

The notion of archives is key to understanding my total engagement in collecting the art of the Avant-Garde. This is because an archive is a public collection, a type of public institution which collects and makes public the documentary heritage. Since archive is multifaceted, it is public, but it is also a part of the collection. My collection is, in that sense, a public archive which holds a task to keep all the documentation of the activity of a large group of artistic phenomena in the period of Avant-Gardes and Neo-Avant-Gardes. Of course, the responsibility for such tasks falls also on the state, through its institutions and museums, but also due to the entire context of culture in my country. The real collaboration between the public and the private sector is still missing in many part of culture. I have offered my collection to the public, to the experts with these exhibitions, through the website (www.avantgarde-museum.com), also with loaning the works from my collection to all who have the intention to keep researching this art. In this way contemporary archivistics is done in the world. It faces three key questions, the same questions I face: how to select and divide the documents which need to be stored in the collection’s archive; in which way to make the material from the collection available to the public; how to handle the material, or how to share it with others. Since the items are delicate material and there are a great number of written records, material on paper, which has great significance in researching the specific relationships of artists all across Europe, I face a serious problem of storing it and finding a way to examine it. This was the starting point for my project of digitizing the collection, and in this manner, using software, to make the entire collection available, to make it a public document. Thinking on the models with which I would make my collection open, I have come to some interesting insights by researching the various written documents from the collection. This brought up an exciting questions: how did this “network” of artists managed to resist the network of secret services, which surveilled everything, even the artists? How did the artists fight back, hid, communicated, how did they manage to stay “free” using their own language? Because of this, I would love to see the archives of the secret services, the records on the artists which are in them. A research of secret services – their methods, deceptions, hiding, monitoring – would give insight, unveil, and make the history of the Avant-Garde even more transparent. I think that only through this approach my collection would set questions which, at least for now, we cannot answer with complete certainty – how was did time period and what relationships determined this art. I hold that this ontological approach to the Avant-Garde “being” must be done, the analyses must be exact and based on factual evidence, and this is exactly what I am doing – collecting everything that could make that happen. This is the place of the term of “archive”, as an important section in the Museum of Avant-Garde, which I plan to build.

If you had to list 5 of your favourite works/artists, which ones would you point out and why?

Of course it is possible to choose five or more artists. However, a long time ago I had changed the criteria of my collecting. It is possible to collect works based on individual “credits”, or market values of some artists, it is possible to build a collection on key works etc. But my concept is based on an objective view of one era, with the participants of the Avant-Garde scene, but also on the objective placing of the collection in the context of the whole history of art. Due to this stance, I am still in the phase of establishing the collection. I think there is still a lot of work on rounding up these phenomena on a global level. This means that the collection is nearing to the point of sustainable development, it reached a level which needs to be sustained, especially since the impacts of the collection are visible now. Many artists today have their contemporaries, role models in the Avant-Gardes and Neo-Avant-Gardes. It is like there is a continuing tautological line, continuing further. My engagement with the enhancement of the collection is becoming more complex constantly, and because of that I find it very difficult to have my favourites in the collection, or some favourite works. Simply put, that does not even cross my mind, even subconsciously, privately or publicly. This stance – that I do not want to single out anyone from the collection, could as a consequence make my collection “boring”, since the museological practice is based on the principle of choosing the invaluable worth works. However, I am guided by the principle that the moral principle is fundamentally important, and that for this reason the participants in this art are equal – exactly because their moral and ethical stance was above all subjectivism. The biographies and destinies of these people are fascinating, their consistency in rejecting all compromise with the totalitarianism of the political elites is fascinating, as well as how they dealt with repression, and the commodities market traps which never sees the artistic value, but pays for less valuable art. Those artists are the historical consciousness.

You put a lot of energy into gaining public visibility for the collection; do you plan to establish a museum or a place where the artworks will be visible permanently?

The series of exhibitions is part of the strategy, steps towards the final placement in the Museum of Avant-Garde, in an object which would give visibility to material in my collection. Until then, the exhibitions help me gain a complete insight in the possibilities this collection holds. There exhibitions are a special type of “modelling”, or trial set-ups of the future museum. It is not simple to present over 250 artists I have in my collection. The most recent exhibition in Milan, on which we presented 120 artists, showed the architecture of the permanent exhibition or a model of how to present diverse concept which can be built from the totality of collection. What we are doing now with the on-line segment is setting up the concept of the future Museum of Avant-Garde, especially having in mind the incredibly dynamic expansion of museology around the world – both in the field of artworks, as well as architecture. We are discussing the establishment of the only Museum of Avant-Garde in the world – it will be truly the only one, as there is a large number of museums in the world that have works by the artists of the historical Avant-Gardes, but there is not a special place where this material could be seen in one place. It has now become a central political, cultural issue – how to reconcile a certain kind of periphery, in which Croatia or an entire part of East Europe is now, and the centre, the great museum systems of Europe and the West. The relationship between the margins and the centre constitutes a redefinition of the status of art and artists; it implies the writing of a new history of the art from the East. In this context you must think about the processes of convergence of attitudes in the curatorial practice, which now increasingly creating theoretical platforms which align the entire artistic legacy on the East/West divide. All items that I have listed can be corroborated by the fact that, since 2002, we have been a part of over 85 projects – exhibition we organised independently, working with the Institute for the Research of the Avant-Garde, or in collaboration with institutions by loaning works from the collection. Speaking on these collaborations, I can mention that works from my collection have in recent years been a part of exhibitions such as “The World Goes Pop” in Tate Modern or “Ludwig Goes Pop + East Side Story” in Ludwig Museum in Budapest, as well as Kassák Museum in Budapest, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Haus der Kunst in Munich,… Works from my collection are currently in large European exhibitions – besides the Milan exhibition, which closed just recently – “Non-Aligned Modernity. Eastern-European Art and Archives from the Marinko Sudac Collection”, works are also on the “Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945 – 1965” in Haus der Kunsts, Munich; “Art in Europe 1945-1968. Facing the Future” in ZKM Karlsruhe; “Notes From The Underground. Art and Alternative Music in Eastern Europe 1968-1994 in Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi; “Slovenia and Non-Aligned Pop” in Maribor Art Gallery. After this dynamic sequence of activities, it is important for me to show the public what it means to establish a museum of Avant-Garde art in Croatia as a regional, highly-professional institution, which will create optimal conditions for the safe-keeping, researching, and presentation of Avant-Garde artworks in the framework of contemporary museology. It is my goal to create a strong exhibiting, information and creative centre in Croatia, which will be able to set itself as a symptom of the process of decentralisation of cultural exchange with the world. And the key goal is to permanently set up the Museum of Avant-Garde, a museum which would fulfil all the necessary standards of contemporary museology, including those for the establishment of a permanent exhibition of the 20th c. art. Museum of Avant-Garde must be a kind of “central” institution for other galleries and collections which hold his art in this part of Europe, and in that way assert its status as an institution of national significance, but with a very clear legal status of private property. Those other, technical and organisational segments of the future Museum, are based on the question of redefining the notion of a museum institution as a structure that gathers, keeps, researches and presents artworks of one historical period on one side, and on the other, as an institution which is seen in the context of new, changed views of art itself, of artistic and museum practice with base terms of Avant-Garde – Neo-Avant-Garde – Post-Avant-Garde. These terms define the role of the future Museum of Avant-Garde.

The list of artists present in the exhibition Non-Aligned modernity is impressive. Who are the artists you are currently following and do you have a personal relationship with the artist you collect?

The number of artists is truly impressive, and with that the fact they all together belong to one ideology of Avant-Garde, yet they simultaneously have a special, unique expression. They have completely different social, educational, cultural, psychological surroundings in their respective countries, and all the while they speak with the same language of Avant-Garde. The minds of these people are in a way cynical, best seen with the Dada artists. Today theory calls this cynicism a metaphor, which is, in the new artistic practice attributed to the end-of-century Post-modernism. Cynicism expands the space of freedom, and the Avant-Garde artists have recognized the capacity of the cynical critique of false values – they played with language, mimicry, used their personal charm, and in this way got their freedoms. It is exactly this discursive potential of cynicism, placed as a specific vernacular of Avant-Garde artists, that can be taken as one of many criteria based on which I could select artists which interest me. I would love most to have one of Duchamp’s works in my collection, exactly because his ready-mades are based on interpretations that place a non-artistic object in the context of art history. When the message is conceived as cynical, it is such in its very essence. The artists in my collection are doing the same – they use cynicism, not to create new forms, but to bring forth new definitions of society and art. In this sense, I can name names, of artists who are both cynical and melancholic, somehow more worried about society that for themselves. I have emphasized these two terms on purpose – cynicism and melancholy, but these are the elements I have recognized in the artists I have met over the last decade, as well as through the five years of the “Artist on Vacation” project. The world today, the Post-modern age we live in, can be dubbed the Age of melancholy, an age in which a great number of artists feel the lack of sense. They know that the break of the historical progress brought in the break in the importance of an individual, which is slowly losing itself in the Neo-liberal spectacle. This spectacle is a semblance of joy, short-term, lasting only as long as does the spectacle.

I must speak here about the theorist Matko Meštrović, a part of his archive is exhibited in the “Non-Aligned Modernity” exhibition. He is surely the most important phenomena with whom I meet and work with. His theoretic work during the turn of the fifties to the sixties, when he was associated with the New Tendencies movement, and his parallel engagement in the Gorgona group, until today, is something I want to use to explain this melancholy paradigm. In his work “Formal Economy and the Real Historic World”, Matko Meštrović discusses all the deep contradictions in the logic of capital as the primary carrier of the globalisation process. This then contributes to creating a contradiction – the demise of factory production and the rise of financial capital. So, there is a large volume of capital, wealth, gathered in a single place, while on the other end there is misery and poverty. Meštrović wants to say that the Capitalist work ethics has lost all meaning, that it is impossible to create a new community without ethics. This is the argument for the melancholic mood of the artists that seems to prevail when I talk about the collection, their lives in the last decades, as well when we talk about the destruction of the ethical values of our communities in Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia,… This is what occurs when we try to see into the possibilities of the alchemical process and by analysing the art of the Avant-Garde, we find a new view on ethics.

In a time when cultural budgets are shrinking all over Europe, Croatia included, how would you define the role of the private collector/collection? Do you cooperate with any Croatian public institution (museum, university, research centre…)?

The interest for culture has never been higher than it is now all across Europe, but the interest in art has never been so low. It is a paradox which seeks many answers. First and foremost, what is this culture and this art, how did this discrepancy come about etc. Culture has become an important category of economy through the development of cultural tourism. From that point, in the last decade, there has been a great expansion in terms of building new grand museums, fantastic architectural accomplishments. Nicolas Bourriaud, in his thesaurus of art history, set architecture as an integral segment of art. Hundreds of thousands of tourist visit museums, there are dozens of biennial exhibitions around the world, and there is a new art market system which operates through art fairs, there is an expansion in the number of private collectors… In some countries, there are laws which regulate tax reliefs for investing in culture. So, there is an incredible dynamics of culture on one side, and on the other, there is artists’ reaction to those processes. The artists “separated” – there is a group of star artists, close to the museum cartels, there is a “league of art champions”, and many artists outside of this first league have connected themselves with private galleries and try to work with private collectors…. However, what I want to point out is the impression that comes from this sort of cultural offerings on the creation of artists today. Their art had succumbed to market influence and became depleted, with a tendency towards spectacularization and shock, but one can see a very low level of art in this. The Neo-liberal capital had used up its ethical aspect, and created a ruthless market, like a black hole sucking everything surrounding it. On the perimeter of these corporate black holes is culture, as a singular term, the culture which tries to defend art from ceasing. Will the Capitalism black hole suck the culture in as well? Or will culture, arts and society change together, according to the writing of Herbert Marcuse who speaks on society as an artwork. Capitalism has, as Social Realism in Communist Russia before, created a Capitalist Realism – art of the West started glorifying the power of Capitalism. This is not my opinion, but that of many artists I had spoken to. They know this best, since in their minds the ethical aspect is key, the artists are fighting for ethical values of art. This concerns the artists outside of the mainstream system, some of them are a part of my collection as well. I would like to remind you on a valuable result which came from Walter Benjamin’s writing. He connected the material aspect, or the Capitalist context, with the function of an artwork in the era of technical production, the multiplication of capital and brining in reproduction in art itself. Benjamin was the first to notice what is happening today. He started from the fact that an artwork, an absolute unique, appearing as such singularly, can now be multiplied, reproduced… and with that, it loses its aura. The artwork gives in to the foray of the masses which now determines an artwork. Marcel Duchamp, as well concluded that the audience constitutes an artwork, not the artists themselves. So this paradox multiplies, since the mass consumption of culture and arts can be a double-edged sword – it can be a symptom of progress, but it can also become drained and harmless. Today, my collection holds a great potential for reaching these conclusions, it contemplates, and it is located between the danger of commercialization and the danger of staying outside of these developments, the danger of losing its aura in the sea of various cultural offerings. In talking with artists, I can conclude that now is the key moment that my collection becomes one of the models of new culture. The conclusion might be that, due to this situation in which the moral, humanistic model of freedom of Neo-liberal (Capitalist) type might become dominant again, it is essential to proclaim a liberation battle of art for the ideals worthy of serving to. This is the task of all of us collecting, contemplating, exhibiting this art – it is the task of institutions, museums, collections, countries… We, all together, must fight that art today stays autonomous as a role-model of freedom. This is one of the messages of the artistic accomplishments of the Avant-Garde, Neo-Avant-Garde, and Post-Avant-Garde I collect.

For some years now, there has been a persistent and international attention for Eastern European neo-avant-garde. How long do you think this attention will last? Would you expand your collection towards more recent periods when this attention decreases?

The interest for Eastern-European art in the West cannot be separated from the process of development of the Neo-liberal Capitalism in the countries of Southeast Europe. This process of convergence of the East and the West in all aspects, especially through the implementation of standards through negotiation, reconstruction of the legal framework, ecology, commerce, culture,… contributed to the process of capital implementation into the majority of the private sector, while the countries are obliged to care on the transparency of the laws. Simply, the Socialist countries have become Capitalist countries. Those are sure prerequisites which expanded the interest towards art. With capital, what also started was a process of a different approach by the art experts – those who base their curatorial practices on the models of competency and problematisation of the found cultural heritage. It was fascinating for them as well to see the works of the Neo-Avant-Gardes in Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary… I need to point out that, before the fall of the Berlin Wall, this art stopped “being produced”, the artists from this side of the wall did not have a place to exhibit – the dominant art of the “post-modern” beat them. In the Eastern-European areas during the eighties there was a dominant post-modern stance on casualist painting, on the informal implementation of Western trends. It was especially the Italian Trans-Avant-Garde, promoted by Achille Bonito Oliva, which contributed greatly to the liberation of artists from the Modernist dogmas. The Eastern-European painters “confiscated-won over-adopted” the tactics of the new German painting, of Italy, of British sculpture… and they created a sort of hybrid art that held the formal iconography of the West. However, through a dynamic production as was such, there came about a faulty principle that the new Trans-Avant-Garde painting or new sculpture was ground zero. The artists did not realise at the start that the art of the Post-modern was, before all else, a continuity of the previous historical occurrences, they did not realise that the Trans-Avant-Garde follows directly on the gathered knowledge from the Avant-Garde, and Neo-Avant-Garde, predominantly in the case of deepening the meaning of the language of art. Painting in Eastern Europe is becoming more critical again, it is not painting without a concept any more. The Perestroika artists in Russia directly continued the art of the Russian Avant-Garde, of Tatlin, Rodchenko, Goncharova etc., they stared working on the historical legacy of Avant-Garde art. I should mention Oleg Kulik, who is internationalising the art of the East. Similar occurrences can be seen in Croatia as well with many artists, and in Serbia, where the artist Raša Todosijević is very directly, in his installations, pointing to the developing clerical aesthetics. This is the framework which arises after the fall of the Berlin Wall and after the implementation of Capitalism in the Eastern-European countries. Without this context, there wouldn’t be an essential interest in Eastern-European art.

With this elaborate answer I want to say that there is not a trend, but that this is about the ideological phenomena arising inside of the socio-political changes in the world, and especially in Eastern Europe. In this context, there appeared a number of institutions, curators, collectors, who saw that and started putting together the puzzle pieces of a global art map we are now discussing. The key question here is the fate of these collections and the destinies of artists who created this art. What is the way to go about protecting this art from the merciless Capitalist model of commodifying everything? With this I want to say that the dominant Fordist model of Capitalism settled itself in the East. The Eastern-European countries had accepted the classical model of production organisation from the start of the 20th c., and this gave way for the first wave of private capital accumulation. The assembly line production contributed to the emergence of a certain financial-political oligarchy, and with a social surrounding, unique to transitioning countries, was created. This accelerated colonization of the East disturbed all goods markets, including culture as a commercial category. However, in the last ten years or so, after a great number of countries entered the European Union, a Post-Fordist economy model established itself – a model in which one works increasingly with knowledge and values. The control of the values of the social field became more rigorous. With this, a philantropical class of society way created. This class finds culture and art to be its core activity which must be placed outside of the ideology of consuming everything, i.e. to forgo the attitude that if one shops, one exists. And finally, the use of the phrase “if I have art beside me, I exist” is on the rise.

In talking to some artists on these global changes in the societies of Eastern Europe, where the interest in culture and art is increasing, but the interest of capital for owning this art is also increasing, we concluded that this art must be protected under the wing of a new Museum of Avant-Garde. Museum of Avant-Garde for now exists in its virtual edition, and I want to make a physical structure. This connotes treating this art as heritage of invaluable significance for the global cultural heritage. I am confident that this is an incredible civilizational capsule which must not be given over to the market, it is invaluable.

Are you also collecting younger artists? If yes what are your criteria of selection and which artists to you consider to be the most exciting?

My collection ends with the fall of the Berlin Wall. But that does not mean I do not observe the art that came after that. A great amount of time has passed from that key event, and it can now be clearly seen which individuals, occurrences, and phenomena arose from that. Those are key historical changes. In the political sphere, there were unbelievable disturbances, masses of people were on the move, people moving from the East to the West, there was civil war in the Republics in the former Yugoslavia, an utopian model which that country had was destroyed, terrible events occurred, the historical chasm between some nations increased, there was a great number of people who started migrating to Europe from the Far East. With all that, where was a technological revolution, from analogue to digital networking. Communication between people quickened, changed… And this can all have an effect on culture itself and art. From this position, I am very present in the observance of all of that, I visit great exhibitions in Europe, but I also closely follow the work of museums, galleries and artists on-line, but I have not bought any work created after 1989. This does not mean that this art does not have value, quite the contrary, it is interesting, and some holds incredible quality. However, I am still preoccupied with collecting Avant-Garde art and the final aim of placing the collection in the Museum of Avant-Garde.

When I try to find the criteria with which I follow certain phenomena on the art scene, I always rely on the criteria of the historical Avant-Garde. With that, I relate to the attitude of artists who do not produce their art out of painterly or sculptural material, but from the same material which makes social relations. These would be the artists who do not create aesthetic objects, but who produce stances inside of the grey zones of society. This is the key criteria, the same one the Avant-Garde artists shared. The list of artists I’m interested in is short, but that does not mean that they are few. It means that my criteria is rigorous, these artists must be aligned with the continuity in my collection.

This does not mean I’m strict, quite the opposite, I’m just trying to figure out the circumstances under which we live today in our given world with the incredible amount of prejudice we have towards history. In other words, as Bourriaud states in his theory of Relational Aesthetics: “An artworks does not need to create an imagined or utopian reality, but to set modes of existence, give models in the framework of already set reality, regardless of the scale the artist chooses.” These are the circumstances in which we live in as well, and the artists capture “life in motion” and in their own way recycle it and bring back to the society. This artistic transfer is interesting to me from an anthropological stance, how can art fill the gaps which society created, which are the means art can enable the development of new cultural and political desires? When such art appears on an exhibition, than my involvement with collecting is valid. I agree with the thinking of some art historians, that an artwork, besides possessing value as a commodity, has also artistic values. These artworks are small, delicate spaces in society, actually spaces of interpersonal relationships. Art must set modes of communication between people, whichever they might be.

What advice would you give to young collectors who are interested in Eastern European art?

I would advise them to do the same as I, find happiness in all of this. I might not sound very humble, but my experience is precious and I gladly share it with anyone who can collect the best of culture – in my opinion, that is art. I have gone through many crises, from the hardest one connected with financing, when you acquire an artwork, and you are not sure if you had made the right call. Then you start learning about each piece, on the artists, you start to understand the context in which the work was created, you start loving what you do. So, it is necessary to understand what you are doing. I never had a material motive, one to make a monetary gain. On the contrary, if I need to use this dangerous word “profit”, I will say that I profited as a person, a person who became a part of the artistic cosmos, a universe in which all the members are valuable – artists, curators, art historians, framers, transport staff, collectors,… We really are all a part of this universe. In was in 1993 when Achille Bonito Oliva stated that transnationality, multiculturality, multimedia are the basic ideas of art. These are the foundations of historical Avant-Garde, ideas close to me, those are traits that are in the very nature of art. Younger collectors, i.e. those who are starting to collect, must gain knowledge on all phenomena of art, they must get education in the widest sense of the words, to know not only of artistic styles, names, but to understand the ontology of art. This is my message, art has helped me understand myself and my place in the art system.

Róna Kopeczky and Fruzsina Kigyós