Artist: Jaanus Samma

Title: Folklore

Venue: Robert Grunenberg, Berlin

Samma’s work aims to locate queer subjectivity and desire in seemingly heteronormative spaces: street corners, public spaces, and folk culture are mined and presented as ripe for sexual and sociopolitical re-interpretation. Combining fieldwork, oral history, and archival research, the artist responds to absences of sexual representation by way of storytelling or semiotic queering, as he recovers loaded symbols and signs or inserts them in spaces where they seemingly don’t “belong.”

In the exhibition, Samma considers the concept of folklore as a type of cultural circulation open to queer re-interpretation. While often considered synonymous with tradition, folklore is a flexible and dynamic medium, distinct in that it doesn’t “belong” to any individual or group in particular. As a set of symbols and stories circulating ambiently within a non-delineated public, folklore constantly undergoes modification, and thus transcends issues of intellectual property. It is both collective and personal, performative and ever-changing, and often stands in opposition to dominant mass-cultural forms.

In his series Sweaters, begun in 2014, graffiti markings found by the artist expressing sexuality or queer desire are isolated and reproduced as decorative motifs on hand-knitted sweaters, which in the process both habituates and domesticates their subversive political charge as messages inscribed into public space. Sometimes presented on hangers or in bespoke vitrines, the sweaters are here displayed hanging casually from a row of hooks, like they were recently used, alongside a series of jockstraps from his 2018 project Mythology of the Toilet, where the artist had traditional Estonian handloom underwear re interpreted as the iconic staple of the gay fetish wardrobe, complete with a traditional fastening system. Presented as everyday objects, Samma works against the sacralizing of cultural objects, and points to their inherent imbrication of sexual desire in everyday life.

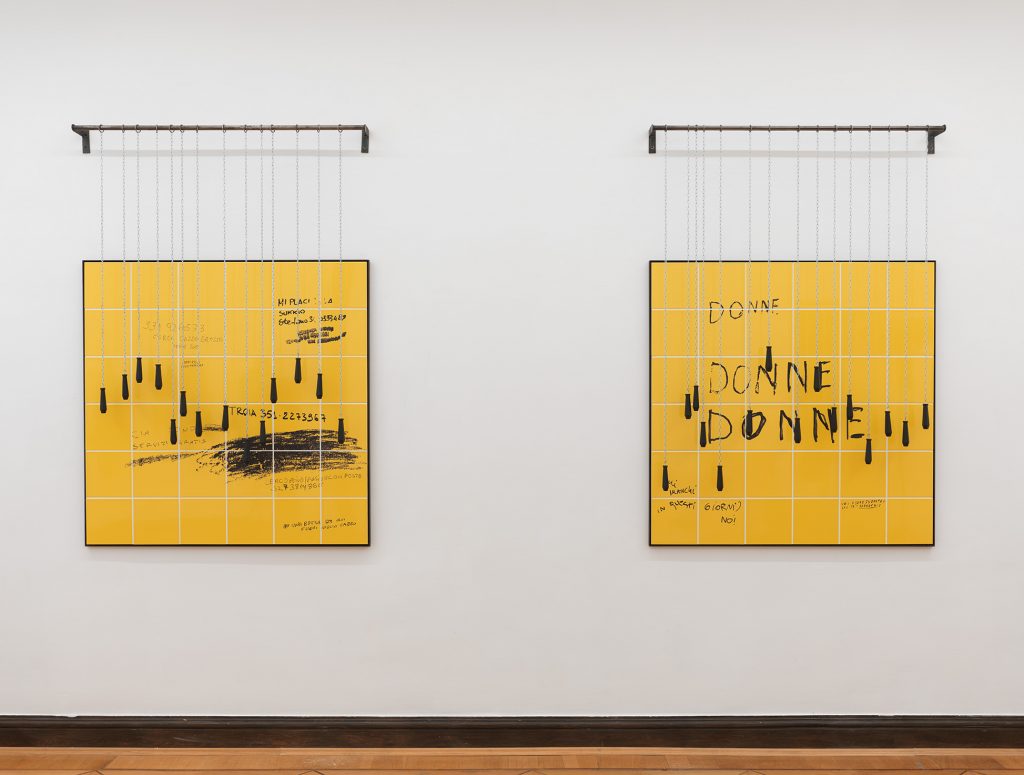

These two critical concerns merge in the series Flaminio Station (2017), a research project where Samma studied histories of gay cruising spaces in Rome, Italy. The public toilet in Flaminio, with its distinct bright yellow ceramic tiling, is one of the few active cruising spaces left in the Italian capital, a busy environment where anonymous individuals circulate along its corridors and cubicles, leaving hastily written messages and phone numbers inscribed on the walls. Samma reproduces these inscriptions, collected by the artist on site, on similar yellow tiles framed by a rusting iron frame, and places them behind a curtain of old-fashion toilet pulls made of rubber. These numerous loaded symbols – of sex, fetish, secrecy, and clandestine communication – make up an idiosyncratic monument to the anonymous community of Flaminio, and solidifies it as its own kind of urban myth that travels by word of mouth, through networks of kinship and desire.

The contestation of tradition and heritage in Mythology of the Toilet is continued and distilled in the artist ́s most recent work, a series of circular drawings inspired by embroidered patterns from Estonian folk costumes. As is the case in many post-Soviet countries of Eastern Europe, Estonian folklore holds a sacred and glorified place in modern society due to its importance as an anti-colonial (but legally accepted) form of resistance during the Soviet occupation. This has resulted in a continued proliferation of folk heritage as a vehicle of national identity that is potentially available to be co-opted by a wide spectrum of political forces including the country’s new far right. By appending folklore to an imaginary traditionalist, anti-Western, and heteronormative past – representative of “the good olddays” absent of both foreigners and homosexuals – this new nationalist conservatism instrumentalizes folk culture to advance both xenophobic and homophobic attitudes.

Opposing such false logic, Samma shows us that nothing, not even folk culture, is sacred, that is, if sacred means heteronormative and stable. By inserting his own portfolio of symbols – such as underwear and jockstraps – as the central motif of folk patterns, the artist aligns the marginal, elusive, and fluid qualities of folklore with queer subjectivity and community. Considered together, the artist asks his viewers to discuss what stories, subjectivities, and signs qualify for circulation in mainstream society – and what instead must operate in the margins, outside the purview of the public gaze and opinion. Could these set relations be re-negotiated – by way of quiet subversion or forms of artistic commemoration?